We all have too many papers to read; in the past I have just dumped a bunch of related papers together with some light summary, to say why they’re interesting. This paper roundup is on evaluation and benchmarking, which has been a theme for me lately.

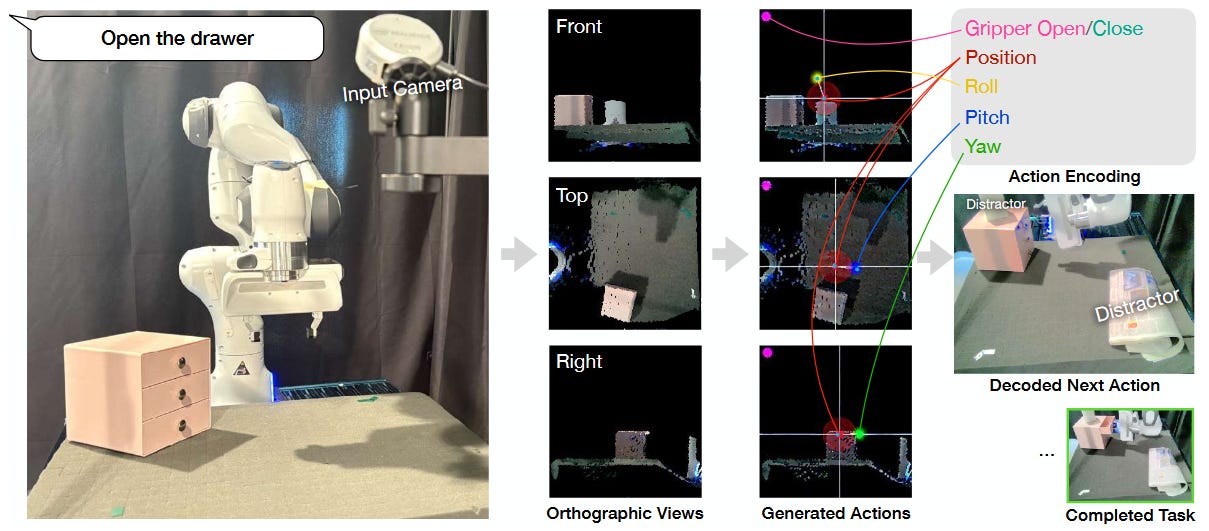

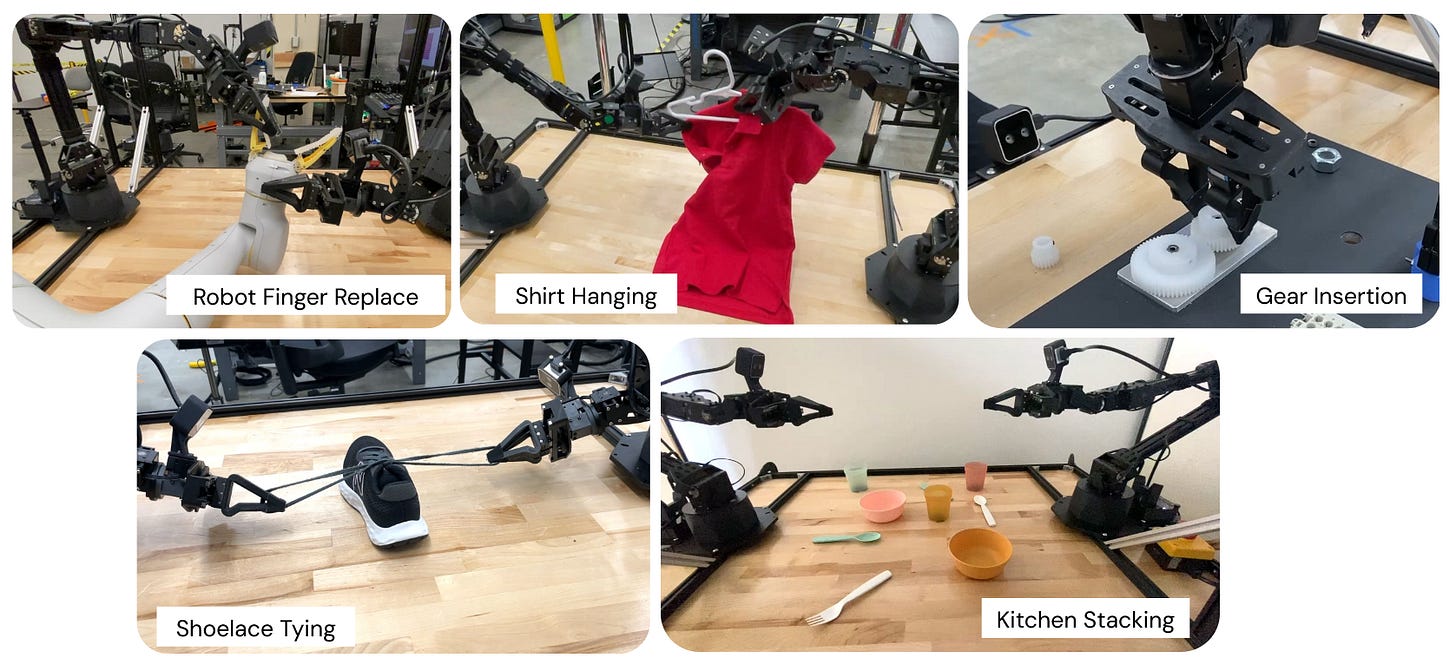

Benchmarking robotics is hard; collecting robotics datasets you can actually use is hard. This blog post is a short overview of a few datasets that might be of interest, both lesser-known ones that struck me as interesting and a few large and well-known ones for context.

You can also use this blog post to scroll through and see what the datasets people are talking about in a RoboPapers episode, actually look like.

If you like reading thoughts on robotics, please consider subscribing. Usually I write more in-depth summaries; this particular blog post is much more minimal and “stream of consciousness” than usual.

An absolutely huge dataset of robotics data. At the time of initial publishing, it had more than 500 skills and 150,000 tasks included, with a wide variety of robot embodiments. It won the ICRA 2024 best paper, and has about half a million authors. Find it here.

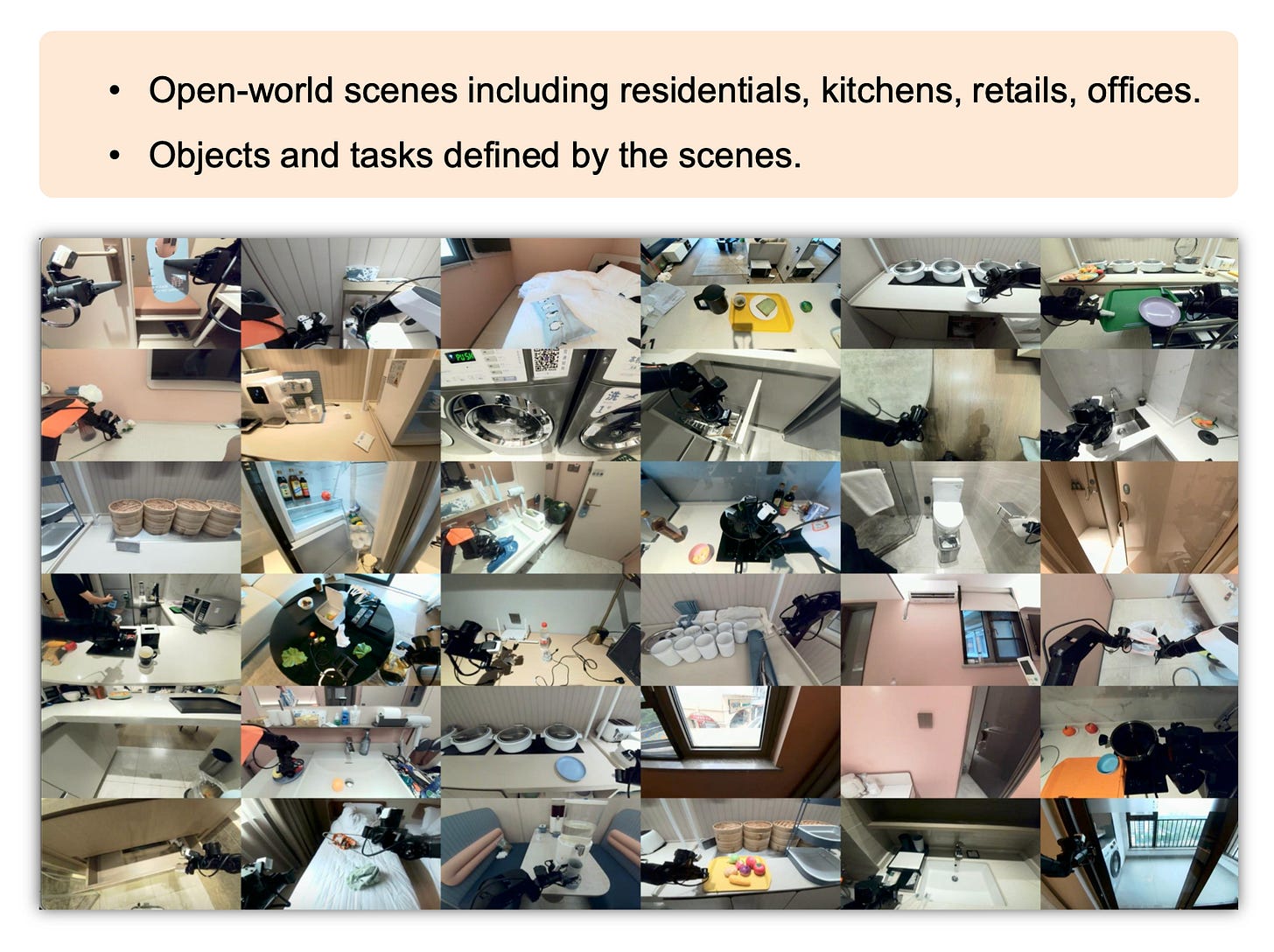

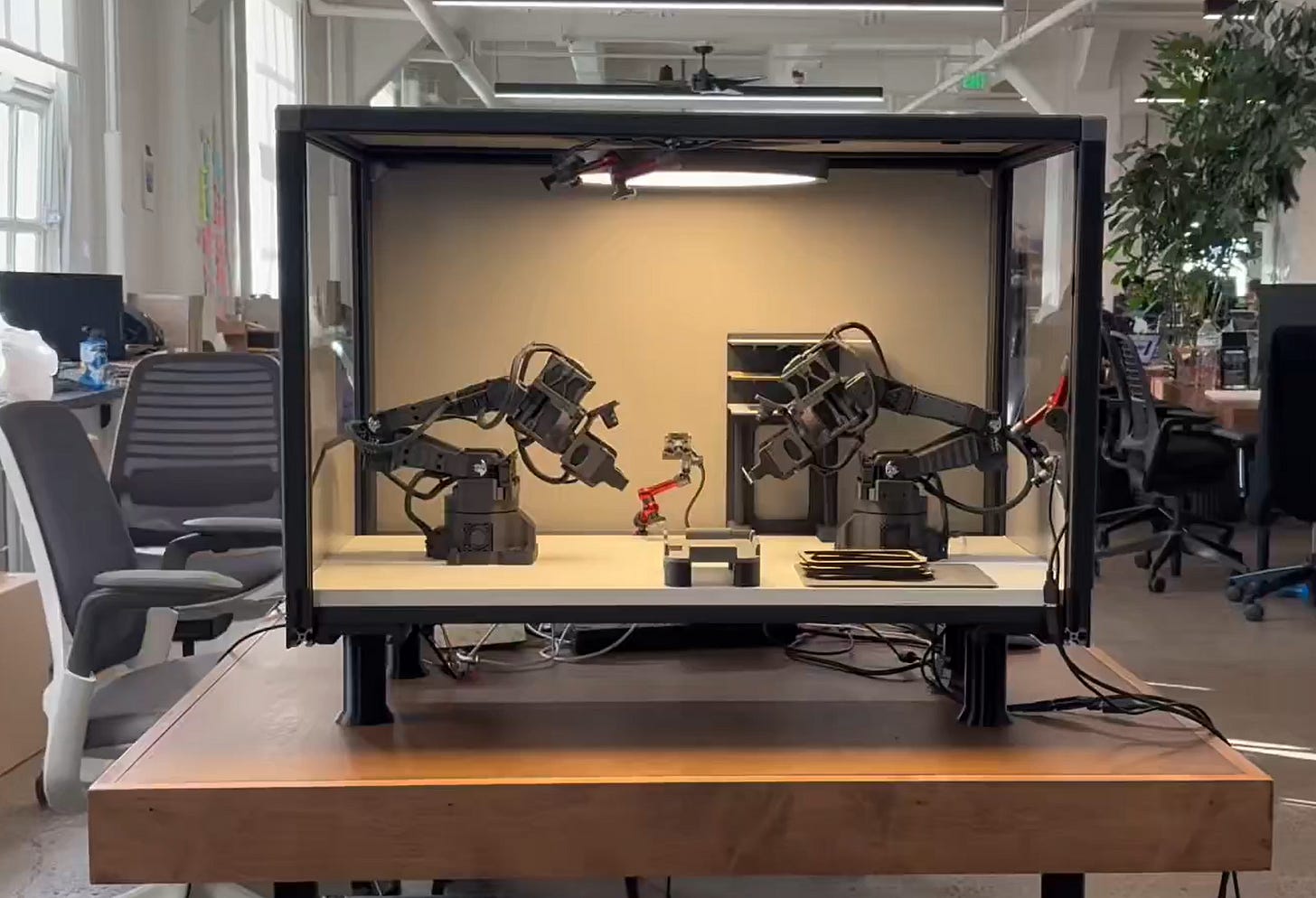

An important subset of Open X Embodiment, and a dataset that’s still heavily used today. Partly because the hardware setup (above) was duplicated across so many universities. Contains a mix of office, kitchen, and home environments, with a Franka Panda arm and a zed camera on the wrist, plus a number of third-person views.

Check out the website for more.

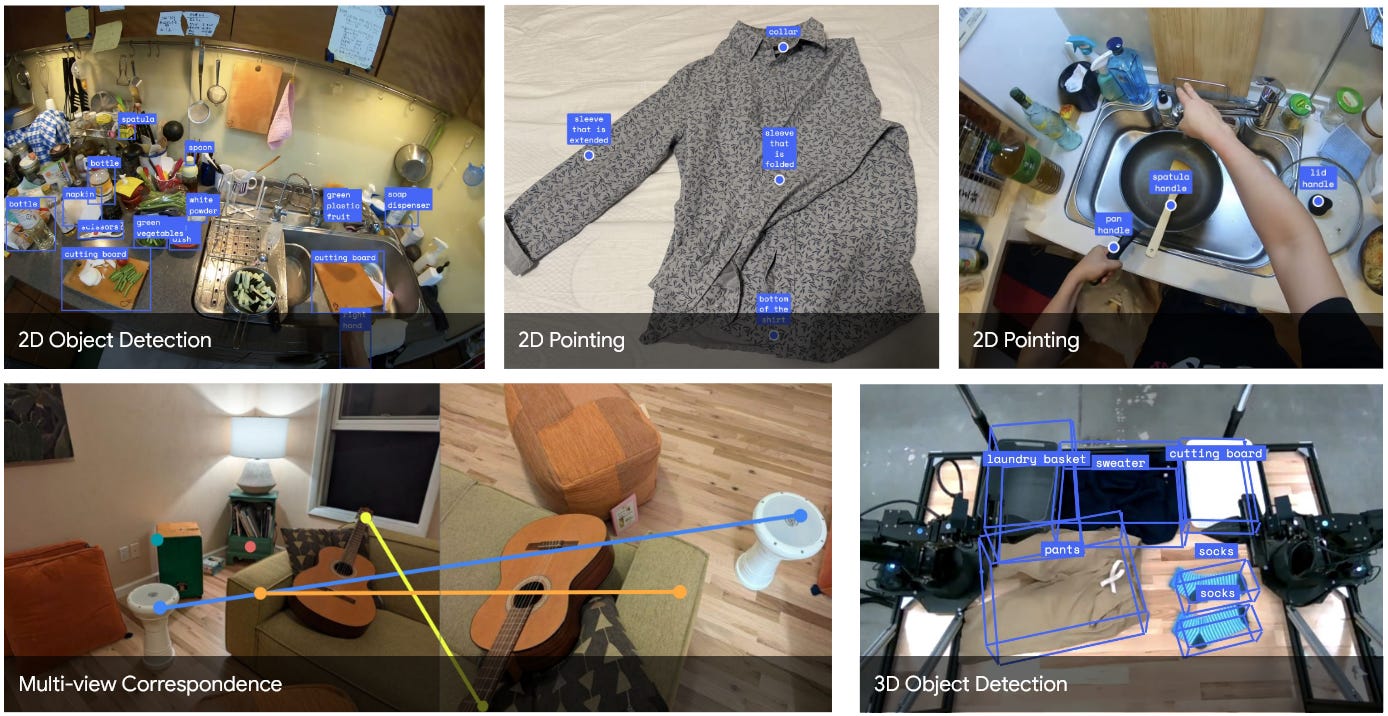

The Build team has released 10,000 hours of video data. 192,900 monocular wide-angle egocentric video clips, collected by human workers in a variety of different environments.

You can find the data here on HuggingFace. And look at Eddy Xu’s X thread.

600+ environments with 120 million frames. Task, language, and 3D hand pose annotations. Often these datasets do not have annotations, so this part is potentially really valuable.

Check out the original X thread from Ahad Jawaid. Github site for OpenEgo.

A task planning dataset, with complex multi-step tasks and question answering. You can find it on HuggingFace here.

A large interesting dataset of human-object interactions. Not sure how useful it is, but given how much object interaction in whole-body robot control has accelerated recently, this seems worth a look. You can check it out here.

You probably know this one; it’s one of the biggest.

With 130 tasks spread out across 4 task suites, it has a lot of variety, and has been used in a ton of research papers so far. The code is also open source.

Contains datasets with RGB information from wrist cameras, proprioception data, language, and PDDL scene descriptions here. These are all high-quality human teleop data, making this benchmark highly suited for learning-from-demonstration research.

A commonly-used benchmark by Oier Mees for language-conditioned task execution. It uses the Franka Panda robot and has a simple setup with some light variation in objects and coloration, together with a good variety in pick and place tasks. Find it on Github here.

A benchmark of 10 base tasks and 3000+ demonstrations which aims, somewhat uniquely, to provide unique, non-binary metrics of performance, in order to give an idea of how and why experiments are failing: there are trajectory smoothness metrics, it tracks environment collisions, etc.

Check it out here. Thread with thoughts; original X thread.

Real-world benchmarking via web socket to your policy. Grad students run evaluations in different university setups.

I’ve written about this one before, when writing about evaluations. I think it’s one of the best ideas for policy evaluation I’ve seen; though it’s still woefully limited in many ways.

See the X thread here, or check out the project site.

A benchmark specifically aimed at sim-to-real correlation. Scan an environment with your phone, use Gaussian splatting to construct a scene, and use a set of tools to create a photorealistic simulation. Ships with a set of “real-to-sim” environments in which performance correlation with the real world was validated.

Check it out here. Robopapers episode.

A benchmark specifically aiming to close the sim-to-real gap. Sedlacek et al. put together this benchmark designed to be a good simulation that closely represents the real world. See the post on this from Evangelos Kazakos on BlueSky.

A video understanding benchmark - but of course video understanding is very closely related to robotics. Basically, how well can video models understand certain physical problems?

Check out the website and the thread on X. There was also an ICCV 25 challenge and associated workshop.

There are a lot of benchmarks and datasets out there; comparatively few (1) have gotten real uptake, and (2) show some actual correlation with real-world results. This is still an active area, and I personally am very excited about potential for real-world benchmarking like RoboArena (though it’s very expensive).

Ultimately the best benchmark is the real world — fortunately, with common platforms like the Unitree G1, we can expect people to open-source code that others can immediately use and deploy.

Sometimes, you need to raise a round for your robotics startup and the training run just didn’t go so well. Or maybe the CoRL deadline is a week away and the results just aren’t there. Never fear; you have options. Follow this guide and everything will work out just fine.

Let’s discuss how to make your model look as good as possible.

Don’t let other people run comparisons. Remember what happened with Llama 4: if other people can try your model out, they’ll quickly uncover its limitations. If you can keep your model secret, that’s best.

Control the environment of your demo carefully. Lighting, objects, initial robot configuration, and so on. This lets you overfit the demo scene and get really nice, smooth, high quality motions.

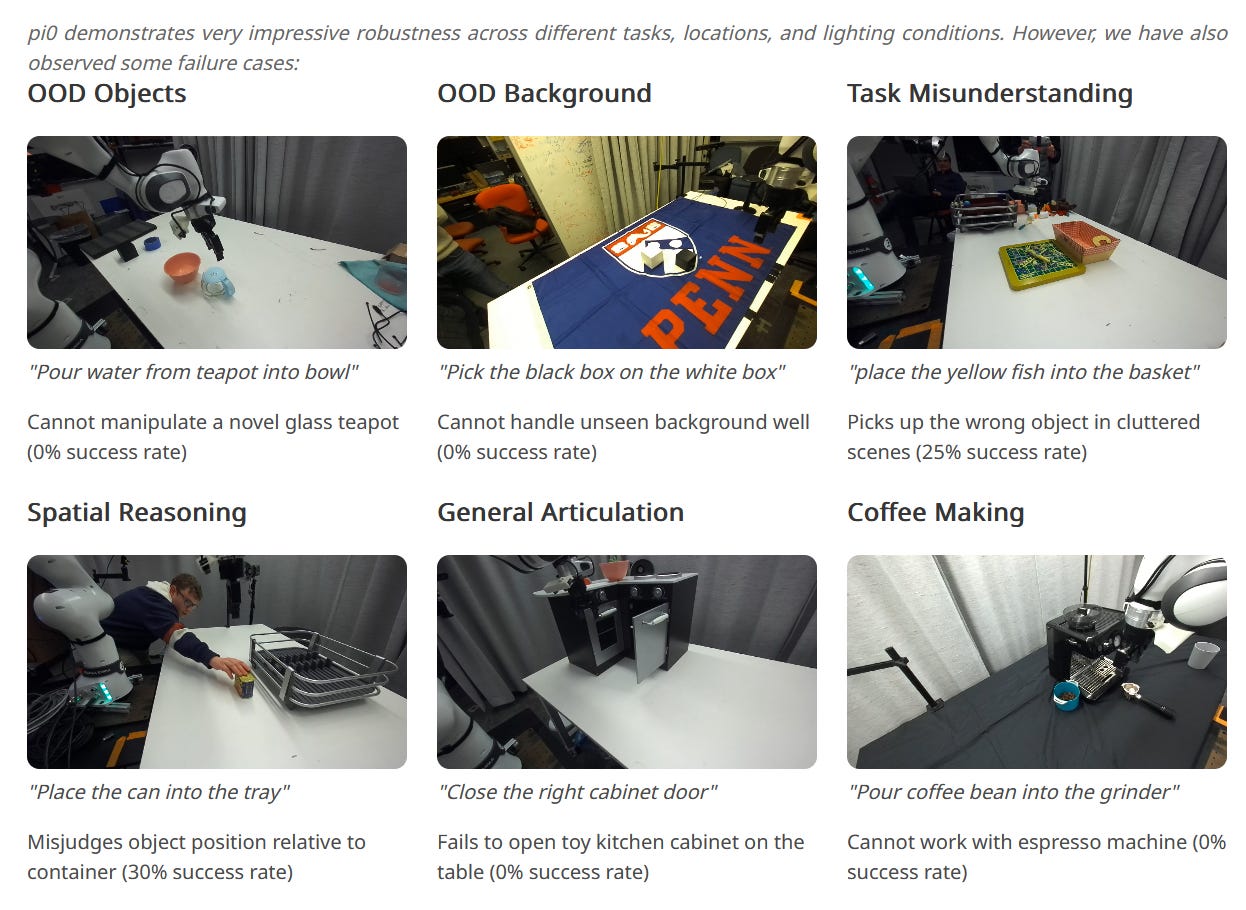

Never show your failures. This one might seem obvious — why would I show failures? — but if people can see where your model fails, they can start to see the limits of what you can do. Only strong robotics papers and results can show failures with confidence.

If you have to let other people run comparisons, choose the people carefully. Make sure they’re only happening in the right circumstances, ones your model supports as roughly in distribution. Absolutely don’t do what Physical Intelligence or NVIDIA do and open source your model so anyone can benchmark it.

When working on the results section of your research paper or blog post, you may be tempted to include some baselines. This is a good idea; just be careful to choose weak baselines so you look good. Octo is a great choice here; it was well publicized but had lots of limitations that weren’t widely discussed.

On the same note: cherry-pick your benchmarks. There are a ton of robotics benchmarks out there, and they all test subtly different things. Importantly, these differences are not obvious to people who are not familiar with the benchmarks involved.

Now, you may be thinking: “Chris, this is all great advice; but people will call me out if I follow these rules.” Don’t worry about that. There are so many little things which influence robotics performance: camera placement, arm configuration, object diversity, low-level controller implementation, and so on.

As long as you can make an argument your setup has to be slightly different from everyone else’s, you can get away with a lot. For example; a benchmark I like is RLBench, which turns out to be a very difficult one for many VLAs, and many successful methods on this benchmark instead use motion planning together with a higher-level goal prediction model.

Second, as a result of the above, robotics benchmarking standards are quite low relative to other areas of machine learning. Papers from very famous roboticists get away with these things all the time, and they’re under much more scrutiny than you are. You’ll be fine.

Open source code and models. Not always possible, but always welcome.

Very diverse scenes and environments. Modern robotics learning methods are very, very good at overfitting to a small task distribution — a clean table, objects at most a few centimeters from where they started.

Don’t be afraid to show failures. We all know robotics methods fail a lot; showing these is a strong signal, and also helps qualify where it works and where it doesn’t.

Compare against the current best methods. Pick the best models head-to-head with embodiments and benchmarks they report on. Don’t cherry-pick.

On the same note, I think paper reviewers must be accepting of some results which aren’t as good as other methods; it must be allowable to fail at some benchmarks, or people will cherry-pick.

Almost all of the robotics videos and results you see are, I believe, real — in that they’re doing exactly what the creators say they are. The problem is that because it’s so easy to overfit to a particular scene, and because the limitations of a model are so hard to ascertain from a 30 second clip, it’s really hard to tell whether a team is making progress toward the underlying goal of general-purpose embodied intelligence.

And robotics is hard; just because a team is employing some of the tricks I wrote here does not mean their results are invalid or their model is weak. I am certainly guilty of them all, at one time or another! One of the fundamental issues with robotics projects is that there are so many things that influence performance, that it’s very hard to distinguish the signal from the noise.

On the same note: lots of machine learning researchers from other fields don’t understand how hard robotics benchmarking is. They will often insist on building their own, usually simulated, benchmarks, which invariably don’t tell us anything and just add more options for #6.

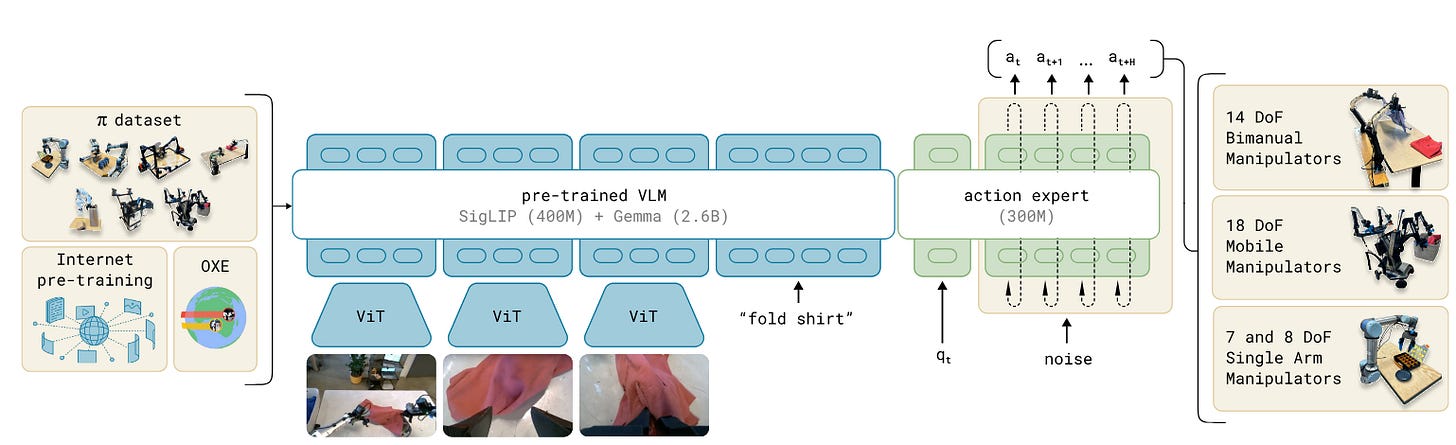

In the end, robotics benchmarking will be solved by having lots and lots of robots, and models that actually work across most of them. More projects like Lingbot-VLA, DreamZero, and pi-0.5 — models that people can actually try out on different robots, use, and openly compare.

I wrote about evaluation a bit in the past, and will surely do so again:

]]>

The release of the Imagenet dataset was a landmark moment for the nascent field of deep learning. This collection of what is now 14,197,122 images covering more than 100,000 concepts (“synonym sets” or synsets) was key in driving and assessing early progress in deep learning, in part because it signaled the ongoing shift from “better algorithms” to “better data,” which in turn unlocked much stronger algorithms. Quintessential, landmark deep learning papers like Resnet and ViT were evaluated on ImageNet.

The dataset has many nice qualities: compared to other popular vision datasets like CIFAR-100, ImageNet has much more variety; it has high-resolution images; a method working on ImageNet tells you something (not everything, but something!) about whether it will work in the real world. But it’s still manageable: most “Imagenet” results stem from Imagenet-1k, a clean subset of 1,000 chosen object classes (“Golden Retriever”, “Sofa”, et cetera).

But this was a very, very controlled problem: image classification; i.e. “which of these 100,000 classes does this image that I am looking at belong to?” Image classification is easy: the problem is clean, it’s well defined, it’s not going to change or fluctuate. It is, in short, it fails to characterize systems which operate via repeated interaction with their environment as opposed to a one-off image capture.

And so we come to robotics. With the rise of humanoid robots and massive funding for real-world robotics research, it’s more important than ever to be able to tell what actually works and what does not — but at the same time, this is more obfuscated than ever.

Fundamentally, though, there are two main options: evaluate in the real world (somehow!) or evaluate in a simulation. Each have serious advantages and disadvantages. Let’s talk about them.

If you’re interested in seeing more of this kind of post, please like and subscribe.

First, though, let’s discuss the issues with using an offline dataset for evaluating robot trajectories. It works for images and language, after all — why shouldn’t it work here?

An offline dataset might take the form: Predict action given current state observation and task description. However, robotics is an inherently interactive domain; small errors in action prediction accumulate over time, and lead to different outcomes. Good policies compensate for these, and recover from partial task failures.

Without an interactive environment to evaluate in, we can’t compute task success rates, and we can’t determine whether a policy would be useful at deployment time. This leaves us with two options: (1) test in an interactive simulation, and (2) find a way to compare methods on real hardware.

If we need interactivity, perhaps the best benchmark, then, will be in simulation. And simulations are getting more powerful, more interesting, and more diverse all the time. More importantly, we’re regularly seeing previously-impossible examples of sim-to-real transfer. See, for example, Doorman, by NVIDIA, which was sufficient to teach a robot to open a door — though note many difficulties involved in this work!

Simulations are getting more powerful and easier to use all the time. But few of these simulations rise to the level of a usable benchmark, i.e. something like Chatbot Arena, Humanity’s Last Exam, or SWE-Bench Verified.

For robotics manipulation, two of the most notable benchmarks are Libero and Calvin. These implement a wide range of tasks with language conditioning (“push the button", “stack the blocks”), which means they can be used to train and evaluate multi-task policies. For mobile robotics tasks, the most notable simulation benchmark is Behavior 1k, which implements a thousand challenging simulated household tasks.

But there are many more, and they all have subtleties which impact which methods work. This makes it easy to “choose your own” subset of benchmarks upon which your model will perform the best, which renders moot the whole point of even having benchmarks in the first place! Efforts have been made to unify all of these different simulators, like Roboverse.

Another issue is that authoring tasks in simulation is hard. In the real world, if I want to have the robot stack blocks, I go buy some blocks and drop them in front of the robot. In a simulator, I need to get the friction parameters right, masses, make sure contact is working properly, et cetera. I need to implement cost functions (for RL) and success criteria, and this only gets harder as I start to scale simulation up. One notable effort to reduce this pain point is the Genesis simulator, which attempts to use user-prompted natural language to help create environments.

Fundamentally, though, simulations are still hard to work with and an inaccurate representation of the true robotics problem, without sensor and actuator noise, with overly-clean problems, and with unpredictable, often-inaccurate contact dynamics. As a result, there will always be a role for real-world evaluation.

Obviously, comparing performance on a real-world task for robots is the benchmark. But running any kind of evaluation in the real world for robots is hard. In simulation, you don’t need to “reset the environment,” putting everything back where it was before you run again — something I have done many times in my life as a robotics researcher. Fortunately, we’ve seen a couple ways in which this problem might be addressed, especially inspired by recent work in large language models.

When the AI field moved towards large language models, we quickly saw a rapid proliferation in the number of benchmarks of ever-increasing difficulty - benchmarks like Humanity’s Last Exam fit the Imagenet mold of: here is a dataset, see if you can get the right answer.

But benchmarks quickly saturate; and they never solve the “real” repeated-interaction, high-dimensional data problem we actually care about, whether the goal is language or a robot. One evaluation method which exploded as a result was Chatbot Arena: a platform in which a user comes up with their own prompt, it is sent to two different LLMs, and the user chooses whichever response was better. While the particular implementation has not been without issues or critics (especially notable is Llama 4’s apparent benchmark-maxxing), the approach is scalable, in that it doesn’t require running a full sweep of all possible queries every time. While it’s not perfect, because no two evaluations are the same, it gives you an ELO rating which gives an idea how competitive every model is with other options out there.

This is a great fit for robotics, where similarly, running individual evaluations tend to be extremely expensive. Tournament-style evaluation most useful because it minimizes the number of expensive evaluations you need to run in order to see if it works; crowdsourcing queries also helps prevent overfitting to the benchmark (which was a perennial problem in a lot of computer vision research, and persists in many fields to this day).

Examples include RoboArena, which is a community-run cloud service for evaluating robot policies. Your policy gets executed on the cloud, and you just need to provide a service exposing it. This does limit the kinds of tasks that can be evaluated, though: latency will always be a serious issue.

The authors of the large humanoid robot dataset Humanoid Everyday are also planning a cloud service for evaluating robot policies on a real Unitree G1 humanoid; you can check their site for details (as of writing, it still says it’s coming soon) and watch our RoboPapers episode on Humanoid Everyday to learn more. You can also watch a podcast episode on RoboArena while you’re at it!

All this is very limiting, though. Maybe we should just expect that people will just own robots upon which standard policies are expected to work, so that they can do their own evaluations on their own problems.

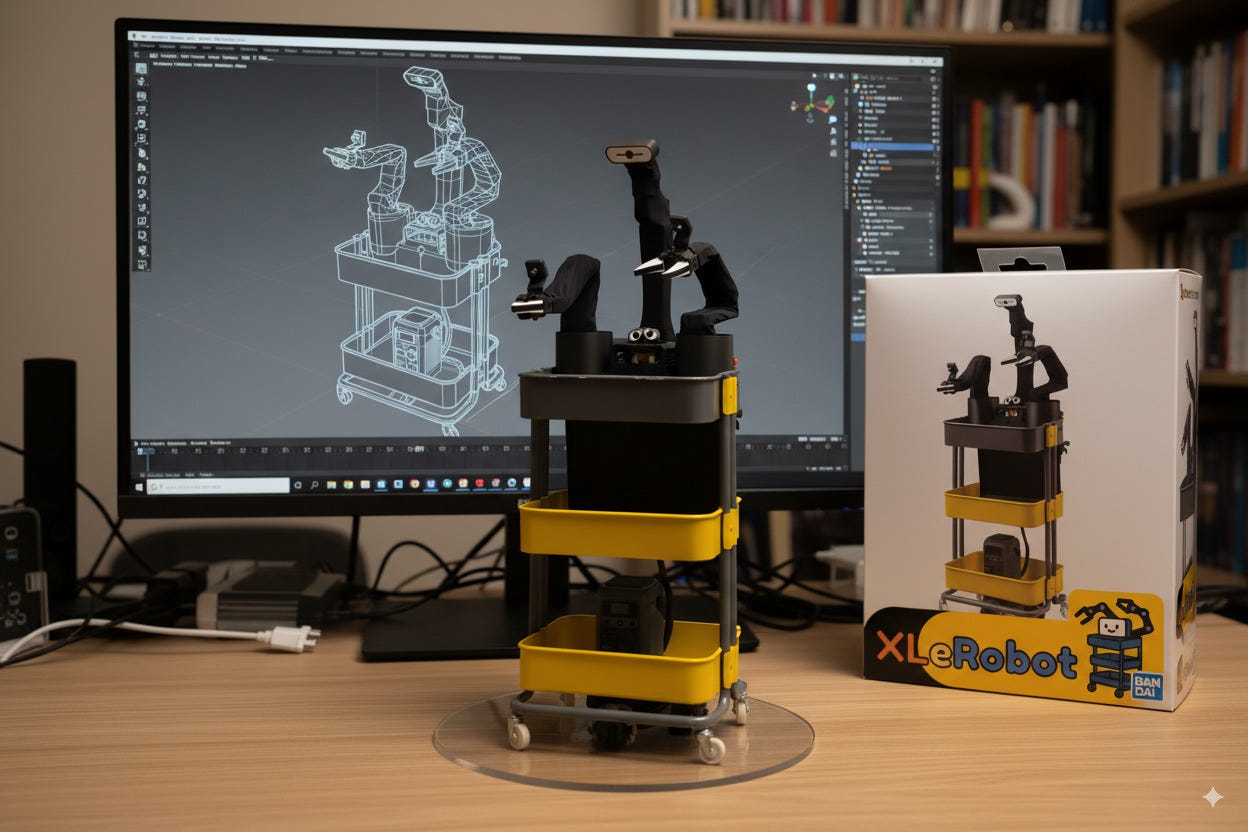

It might even be possible for something open source to take over, something that I’ve written about in the past. The HuggingFace SO-100 arms have seen some significant uptake in the hobbyist community, though very few have made their way into academic research papers that I’ve seen. We might see mobile versions of such a platform succeed; XLeRobot, for example allows for you to, at a fairly low cost, test out different mobile manipulation policies.

Of particular note today is the Galaxea R1. This platform is available for a relatively low cost, and comes in several varieties to support easy data collection, like the R1 Lite. The R1 Pro was used in the Stanford Behavior Challenge at Neurips 2025. You can download a VLA and associated pre-training data for it. It was even used in the recent RobbyAnt LingVLA, which used 20,000 hours of real-robot data.

The most common platforms right now are probably the Trossen ALOHA arms, the YAM arms from I2RT, and of course the Unitree G1. It’s notable how compared to previous systems — available even 2-3 years ago — all of these robots are spectacularly cheap. Robotics has become substantially more affordable, and robotics research more accessible. As a result, maybe the best way of telling which methods are “good” is just to watch to see which methods people build off of when performing experiments with these common platforms.

So let’s recap:

Offline datasets do not work because robots never do exactly the same thing, these errors compound, and all robot tasks are too multimodal for this to be meaningful

Simulations exist and are useful, but are niche, hard to implement, and often missing critical aspects of the real world (usually visual diversity, implementation of interesting/relevant tasks, and high-quality contact simulation)

Real-world evaluation is slow and horribly expensive to run, and can’t match the expectations of other AI fields like language or image understanding in terms of speed.

This sounds dire, and it actually gets somewhat worse; because all of this has focused on assessing algorithms, and robots are not merely algorithms: they’re hardware plus an algorithm. Hardware factors — joint positions, sensor placement, motor types, backlash, heat buildup, and more — often matter more to task execution than the algorithm you’re using.

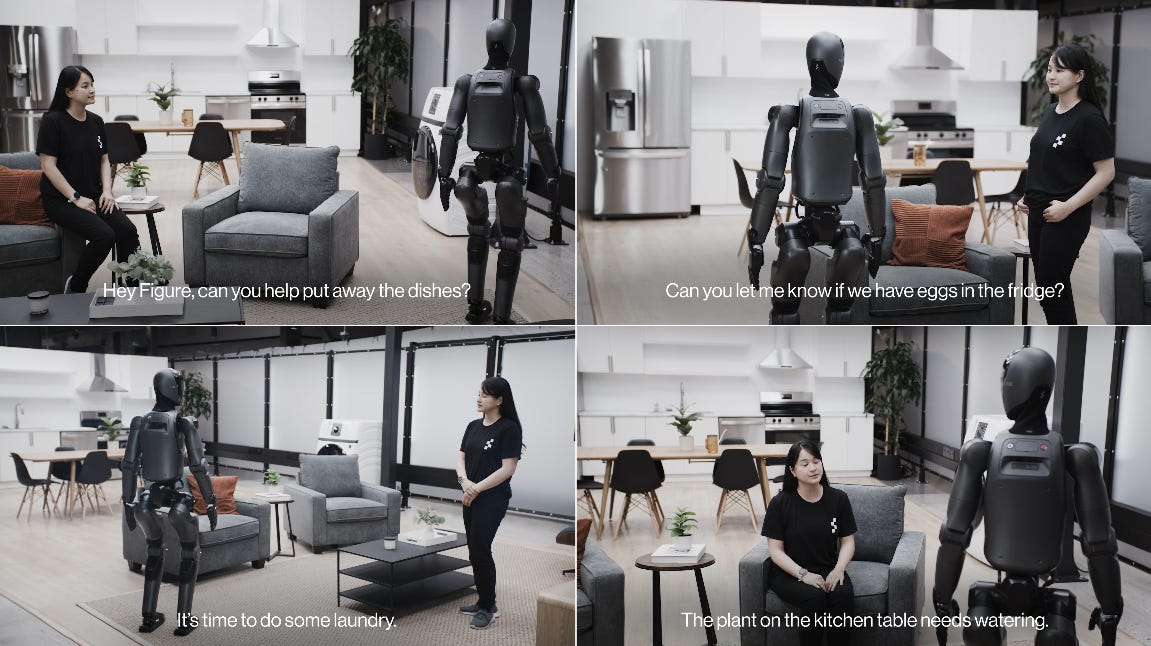

So any “real” benchmark comparison of, say, Figure 03 vs. Tesla Optimus vs. 1x NEO would by necessity look more like a human competition, where participants, say, go to a test kitchen and see who can load a dishwasher the fastest.

We’ve seen the early evidence of such events, like the World Humanoid Games, or the many competitions we see every year at major robotics conferences like IROS and ICRA. These are likely to expand, although major companies right now have too much to lose and too little to gain to bother competing.

On the model side, the fact that you can just download and run pi-0.5 on your hardware, for example, is an incredibly promising start. In the end, though, the answer to the question, “how do we quantify progress in robotics?” has to be “all of the above.”

]]>

Compared to other humanoid robots like Figure 03 or 1x NEO, Atlas is an alien. The product version of the storied humanoid robot from Boston Dynamics has strange-looking, bowed legs; it has an odd, circular head like a lamp, and all its joints can rotate all the way around.

If you want an illustration of just how strange this looks, watch this video from user CIX on X, recorded at CES 2026 in Las Vegas:

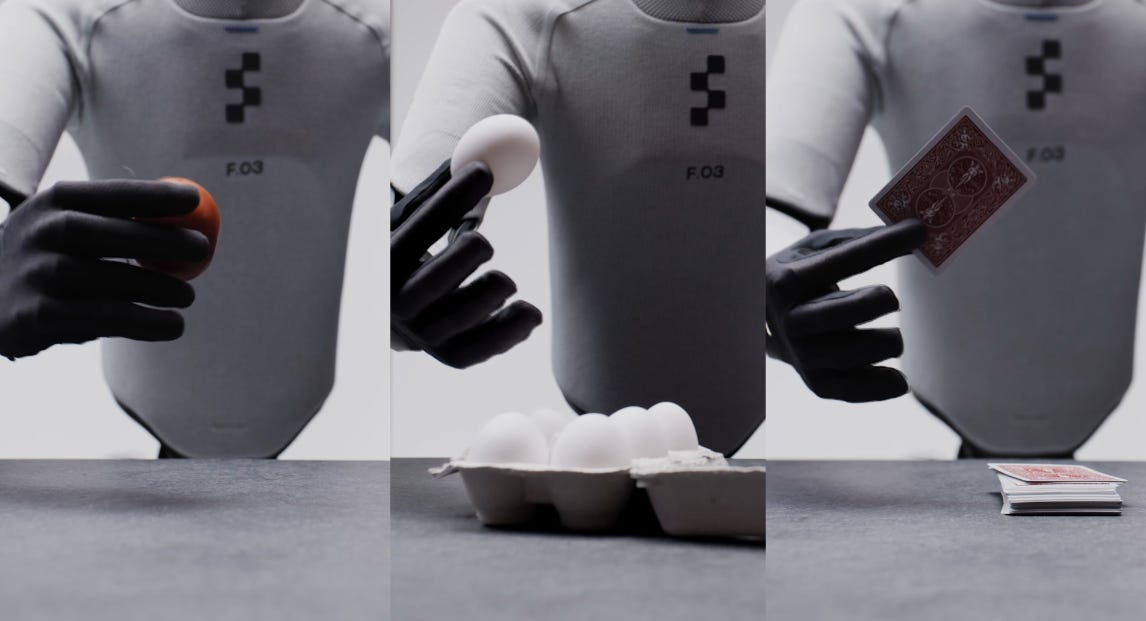

Contrast this with a humanoid like the Figure 03, which was clearly designed to mimic the appearance and capabilities of a biological human, something that I’ve covered before in a previous blog post.

Both of these robots are incredible pieces of hardware, but we must ask, why should Figure’s robot look so human while Boston Dynamics opts for such a strange form factor? Is it just a gimmick that Atlas can turn all the way around? If we’re moving away from the human form, why not just go all the way and make a robot that’s fully optimized for its task like the Dexterity Mech (video from Dexterity):

They do, on occasion, call this beast an “industrial superhumanoid,” and it’s a dedicated pick-and-place monster with a 60kg payload.

So let’s talk about why some of these robots look more or less human than others, and what the pluses and minuses are, with a particular focus on the new design from Boston Dynamics.

When asking why use a humanoid at all, the real question you’re asking is usually “why legs?” And this is an important question; lots of the robots, including the Dexterity Mech shown above, do not need legs. What are legs for, then?

Well, legs allow robots to:

Handle more complex and challenging terrain

Carry heavy things without requiring a large base

The first benefit is obvious — legs allow your robot to climb stairs or cross a debris-strewn landscape. They mean that your robot can be deployed in a wide variety of environments with far less concern about “preparing” the environment for robots.

This, however, rarely going to be a deal-breaker for real-world deployments, as it’s already economical to design industrial spaces to optimize productivity. Amazon, for instance, famously developed new techniques for creating flatter floors in its warehouses to benefit its Drive robots. So, in a real, large-scale deployment, legs are of use for handling terrain — but that’s only a very limited use.

More important is that legs allow robots to be smaller while performing the same tasks. Or, more accurately, it’s because a bipedal robot can perform the same work in a smaller, more constrained area. Because they’re dynamically stable and omnidirectional, an industrial humanoid robot like Atlas can carry a heavy load with a much smaller footprint than a robot like the Dexterity Mech.

This is important because in a factory or warehouse, you’re often trying to fit as much stuff into available space as possible — you don’t necessarily want all the extra space it needs to make a large, high-payload wheeled robot work.

But notably, this does not mean that your humanoid has to look human.

The new Atlas robot has a couple unique design features, courtesy of product lead Mario Bollini on X:

And the unique legs:

With only two unique actuators, the supply chain and cost of the robot can be greatly reduced versus a more human-like design. The fact that the legs can bend forwards or backwards gives it some more flexibility, but also means that the legs are swappable left to right.

And with that in mind, let’s go back to that first video by CIX, where the (prototype, not mass production) Atlas reverses itself during a procedure. Remember when I said the main advantage of a humanoid was working in a more constrained space? This design grants the robot distinct advantages in constrained environments.

Contrast this with the approach taken by competing American humanoid manufacturers like Figure, 1X, or Tesla. Their robots are very closely designed to match the human form factor.

There are a few advantages to this:

Teleoperation is easier. Even if your robot is superhuman, the humans operating it are not — and teleoperation is already pretty hard work!

We have lots of human data already. The internet is filled with human video data; training from this data, as 1X has done, allows you to easily resolve the robot data gap.

Our tools and technologies are all designed to be used by humans. This is a favorite argument of Elon Musk, for example. If your robot is expected to use tools or drive a forklift, you might want it to look human.

It looks and acts human, and people like that. Robots that work around people need to be pleasant and likeable; people might not want to purchase these strange, scary alien beings whose heads can rotate 360 degrees.

There’s a safety angle to this final point as well; if a robot’s capabilities are roughly human, people know what to expect from it, and it’s important humans have a good model of what robots can do if they’re going to be working and living alongside them. This is a huge part of the justification for the design of the 1X NEO, which has very humanlike lifting strength and capabilities.

Personally, I find that there are a lot of holes in these arguments.

I don’t buy that, in the future, we’ll want humanoid robots to use tools built for humans. When transportation in human cities switched from being dominated by horses to dominated by cars, every piece of our infrastructure changed. This will happen with robotics, too, as robots supplant human labor.

It seems very unlikely to me, for example, that humans will be buying non-robotic forklifts for their warehouses in 10 years. Every forklift will be something like a Third Wave robot; you certainly won’t be asking Optimus to go and drive a forklift, because the extra sensors necessary for automation will be extremely cheap.

The same will go for tools; maybe robots will have swappable end effectors, or maybe tools will be specifically designed with attachments for robot hands, but there’s no reason not to think that, at scale, you gain more from good, vertically-integrated design than from building something to support legacy hardware (humans) forever. Indeed, a modular robot like Atlas could eventually use these tools better than a human ever could.

At best, I think the robot tool use argument will be a short-term cost-saver that applies over the next couple years.

This is a vastly better argument in favor of human mimicry, but the cracks are starting to show even here. Human teleoperation data, while essential for robot learning to this point, will not be able to take full advantage of superhuman humanoids.

But there are ways around this, and one is something we absolutely need no matter what: reinforcement learning. Says Atlas product lead Mario Bollini again:

Reinforcement learning is crucial for real-world reliability, as demonstrated in recent works like Probe-Learn-Distill from NVIDIA and RL-100 (both are RoboPapers podcast episodes you can watch/listen to). It also provides a way for us to start with human demonstrations but then improve upon them.

But what about human video data? Certainly, there’s compelling evidence that video data can improve performance with humanoid robots. I’ve discussed the importance of co-training on this blog before: how else could we ever we get enough data to train a Robot GPT?

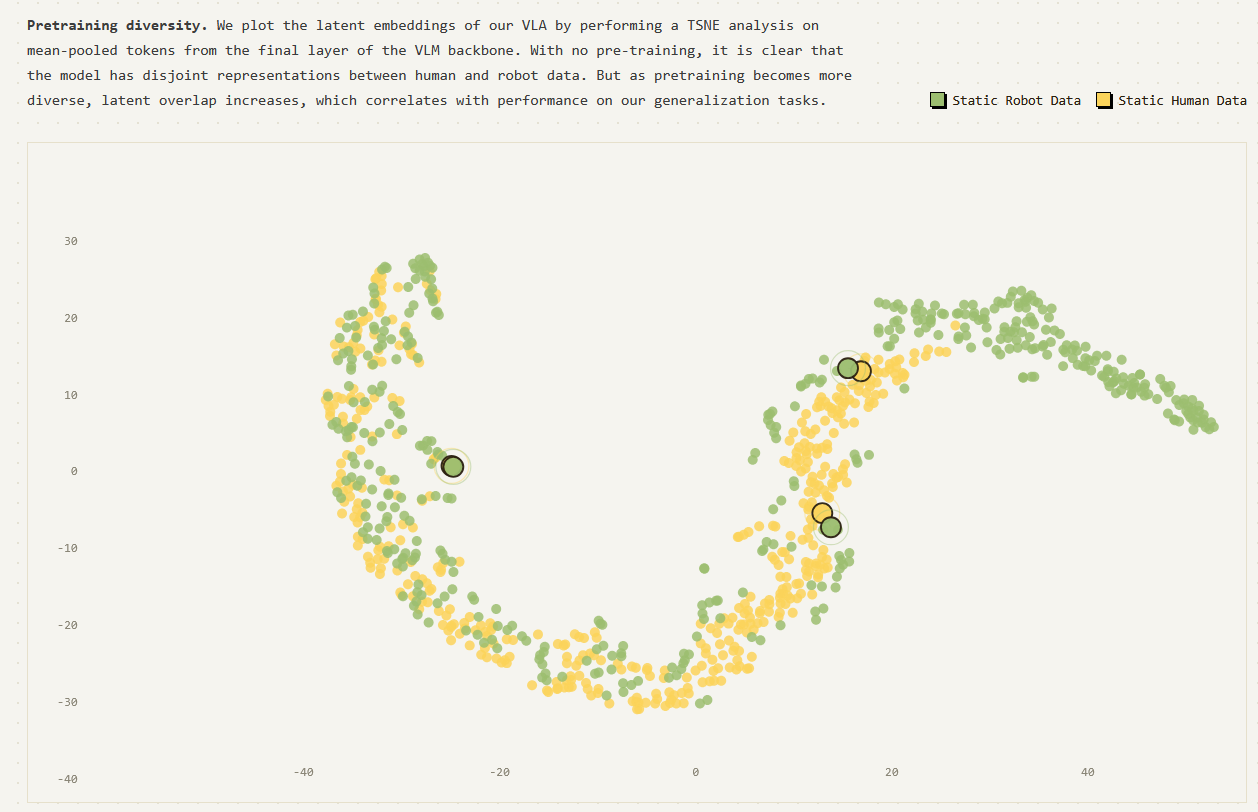

But your robot might not need to be human to take advantage of video data. Take a look at the the recent “Emergence of Human to Robot Transfer in VLAs,” by the Physical Intelligence team. In the plot above, the show how just by co-training on human and robot data, the models naturally learn a similar embedding space for tasks which is shared across the different embodiments.

And PI’s robots do not look remotely human! They’re very simple, lightweight research arms with two-finger grippers. Now, they’re not performing highly dexterous tasks in this case, and this might change, but I see no reason why as long as the robot hardware is capable of a task, that such a shared mapping cannot be learned.

As a final note: I don’t think there’s any particular reason human hands have five fingers. Dogs have five fingerbones, as do whales; neither of these animals use these at all. Humans have hands with five fingers by accident of evolution, nothing more — it is not the product of some optimal engineering process. And so I don’t see why our robots should be limited to that, either.

The humanoid form factor is, I think, here to stay due to its clear advantages, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that it will stay human. The Atlas is an interesting look at a very different vision of what a humanoid robot can and should be, and I think it’s exciting to see it come to fruition with a new model designed for mass production.

I also think there’s a huge opportunity here. As I mentioned above, one advantage of robots that look human is that you understand what humans can do. With a totally “alien” design like the new Atlas, the roboticists can rewrite the script: you know what a human can do, but also what Atlas can do. That kind of product identity will, I think, be very valuable as we approach a sort of “jagged” physical AGI in the coming decade or decades.

Please let me know your thoughts below, and share/like/subscribe to help others find this if you found it interesting.

On December 23, 2025, the Ukrainian military announced that a robot from DevDroid, a domestic producer of combat robots, had held a position near Kharkiv for roughly 45 days against sporadic Russian attacks. Employed by the 3rd Separate Assault Brigade of the Ukrainian Armed Forces, this deployment is emblematic of how these robots are becoming more important in the grueling attritional warfare in Ukraine.

This particular event marks something of a milestone for ground robots, which are used by Ukraine for roles like reconnaissance, resupply, infantry support, and rescuing wounded personnel. Ukraine’s military is particularly focused on robotics deployment, with their goal being to deploy 15,000 unmanned ground vehicles (UGVs) — among them at the very least hundreds of DevDroid platforms — by the end of 2025.

This might seem strange to some: after all, aerial drones are the iconic face of robotic warfare. The DJI Mavic is particularly iconic; as one Russian military blogger recorded, “Mavic means death.” This sentiment — and the overwhelming superiority of Chinese dronemaker DJI — led the United States to implement a ban on the import of such systems from China. Ukraine’s Operation Spiderweb and Israel’s decapitating strikes on Iran during Operation Rising Lion would not have been possible without these transformative platforms.

But there are roles for which these smaller kamikaze platforms are not particularly suited: the war is currently a grinding attritional battle, with brutal trench fighting that has consumed hundreds of thousands of human lives already, leaving both sides scrambling for more personnel to fill the ranks. And, of course, reaching for technological solutions.

We can go on and on about the potential of small, disposable aerial drones in warfare (read my previous blog post, for example). These lightweight, low-cost machines are effective at eliminating enemy infantry and armor; they provide reconnaissance support; they mount ambushes. The Armed Forces of Ukraine received about three million first-person view (FPV) drones in 2025.

But these are not the only aims for warfare. In the end, war is about holding ground. Aerial drones may excel at engaging enemy forces, but arguably they’re just acting as a lightweight replacement for artillery. They can certainly engage the enemy; it’s been reported that drones cause 70% of casualties in Ukraine.

Note, however, that in World War II artillery and air strikes caused 50-70% of casualties. It’s not like the drone is replacing an infantryman. Inflicting casualties, largely, is not their job and has not been their job through much of history. Instead, as Napoleon Bonaparte said:

The hardest thing of all is to hold the ground you have taken.

This is where I think these ground drones come in, and why they have a very distinct role compared to the aerial variety (loitering munitions). Much of the Ukraine war is actually what appears to be almost old-fashioned trench warfare, with human soldiers digging in to hold territory against their enemies.

It may surprise some users that we even want or need ground robots instead of just relying on swarms of drones, so let’s go into what these robots are actually doing a little bit more. There are two main classes of armed unmanned ground robots from DevDroid:

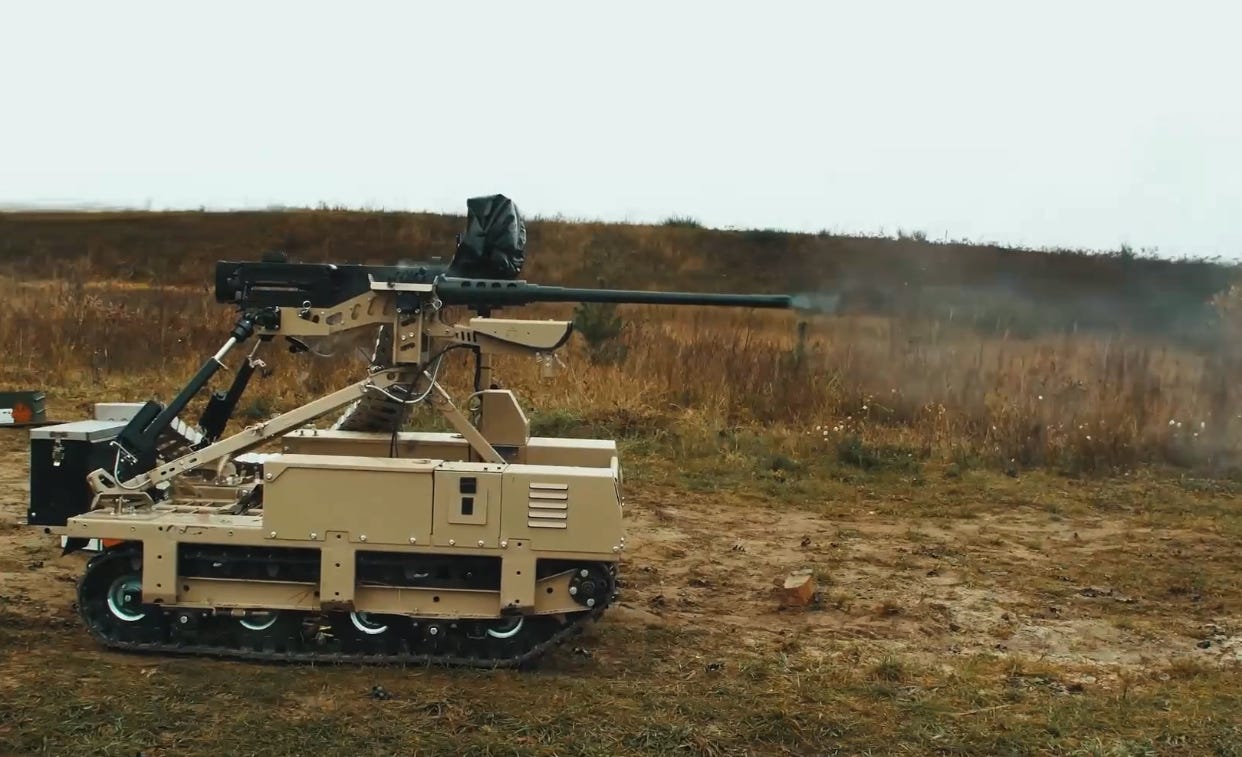

The machine-gun-armed TW 12.7, recently approved for use by the Ukrainian Ministry of Defense

The NW 40, armed with a rapid-fire grenade launcher, used for ambushes against light armored vehicles and enemy convoys, and recently codified (officially inducted into service for state procurement)

In addition, we see many other types of ground robots — kamikaze ground robots, logistics/supply carriers, and others for evacuating the wounded. Many of these are useful for mounting ambushes or for protection against them (in particular using autonomous robots to resupply).

Probably the most important role these robots are serving is to keep soldiers out of line of fire. Robots like the Devdroid or the similar T-700 carry fairly heavy weapons. They can perform fire missions and suppressive fire, and conduct ambushes without exposing human soldiers the enemy. And a lot of what human infantry do, unfortunately, is dig in somewhere and get shot at.

When a robot is "holding a trench” for 45 days, it won’t have spent all of that time taking enemy fire — but it was important to that someone be there, at that intersection of trench lines, who could fire on approaching enemies and take fire in turn.

This process of trading fire creates friction between the two opposing forces, and most likely once the robot starts shooting, the enemy would fall back. If they actually wanted to take that position they might call for artillery or — yes— aerial drones. If no one was there to oppose them, they might just break through, and be able to interfere with supply lines or just seize ground, dig in, and call for reinforcements.

Both sides will start shooting well before any casualties are guaranteed or even likely, at least in any particular engagement. In the American War on Terror, US forces expended something like 250,000 rounds of ammunition for every insurgent killed. But the act of firing on a position — of putting vast amounts of lethal power downrange — forces soldiers into cover or retreat to avoid harm. It prevents movement, and locks down a whole area, even if the engagement between the two forces was very brief.

And this is why a bomb-armed quadrotor — or even 50 quadrotors — can’t do the same job. The gun-armed robots we see here can move around, take some measure of cover themselves, and are armored enough to be quite resistant to explosives and even the occasional suicide drone. They can threaten a very large area — engagement ranges for these weapons run from 50 to 800 meters — and prevent enemy movement through a large part of that area, for days or weeks at a time, all without endangering soldiers on their own side.

It’s a very different part of the puzzle that is a modern battlefield: as opposed to being disposable, high-precision “light artillery” like aerial drones, these robots are acting like infantry or “light tanks.”

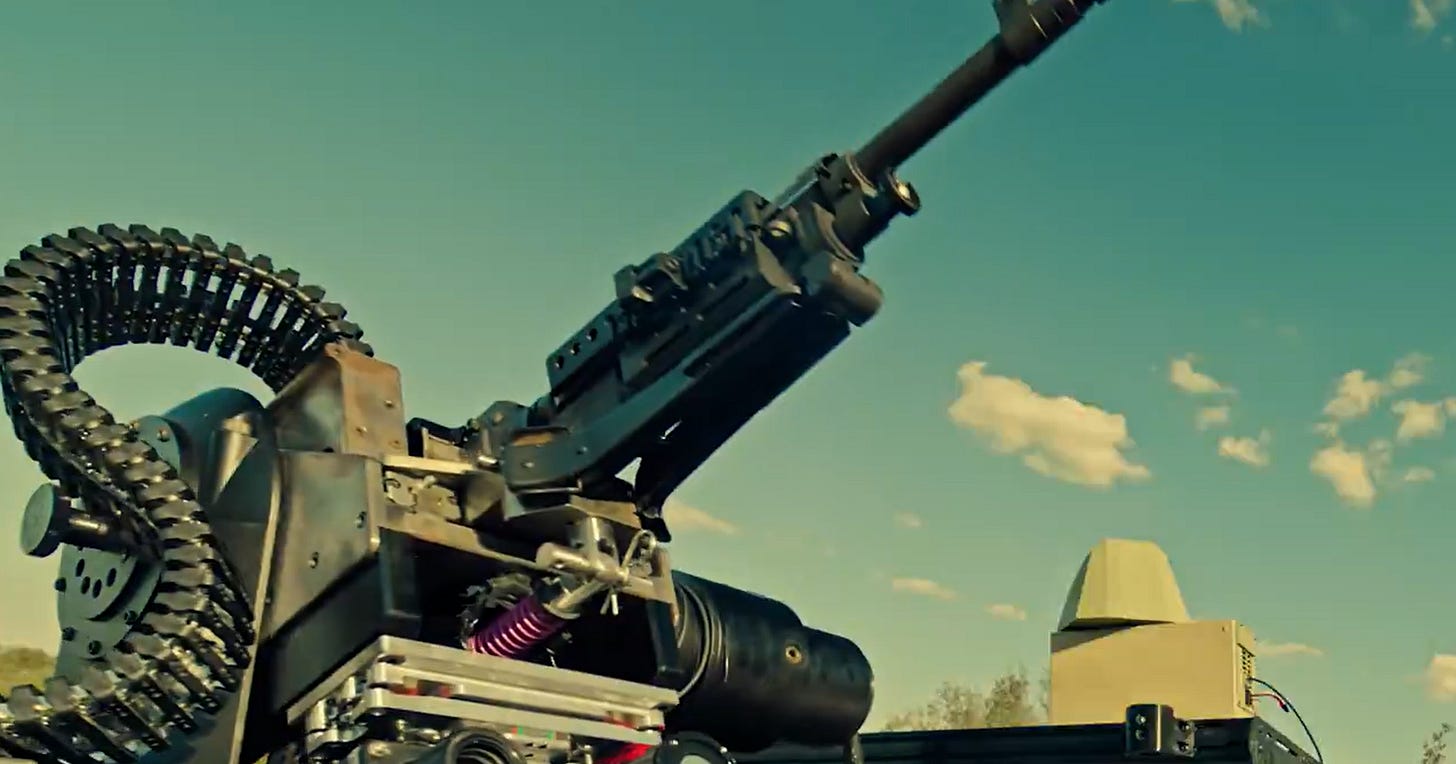

As noted above, these robots are not autonomous. But this is likely to change, and it might not be very long before it does — and the reason comes back to aerial drones. Basically, today’s militaries badly need an economical solution to keeping the “lower skies” clear and their troops safe (or, at least, as safe as it gets in a warzone).

Currently, counter-drone efforts are largely a manual affair, using specially-equipped interceptors which, themselves, are human-piloted FPV drones. More autonomous and scalable solutions exist, but often interceptor missiles end up being more expensive than the robots they are shooting down!

This has led companies like Anduril and Allen Control Systems to start building autonomous gun platforms which can automatically detect, target, and shoot down fast moving drones. Think, similarly, to the Phalanx CIWS on American carriers: these shoot a lot of bullets (relatively cheap) to take out the incoming drone while protecting humans on their team.

There is, rightly, a lot of debate about robots making the decision to shoot against humans, and the United States Department of Defense still says humans will stay in the “kill chain” at all times. But if they’re just shooting down munitions, presumably, there is no issue.

Of course, as countermeasures (to remote operation of these robots) grow stronger, and artificial intelligence gets better, who’s to say that robots won’t start to be trusted with more and more autonomy when handed other targets?

The old cliche goes that necessity is the mother of invention. Many of these current combat robots exist to solve for very specific problems the Ukrainian military faces, particularly a lack of manpower.

But these still feel like they presage future warfare in important ways. These machines will appear first to help hold ground, and to secure the lower skies against enemy drones — but if the need arises, they’ll be doing more than that.

If you like this, or have any thoughts, please let me know below.

To learn more, read my previous article about aerial military drones below.

]]>

When a technology finally clicks, the changes spread faster than anyone expects and have far more serious implications for society. I want to lay out a case here for robotics finally “clicking” within the next few years, and what that could look like for everyone. Technological change happens fast, and nowhere is that more obvious than in the early part of the 20th century.

There were 130,000 horses in New York City around 1900. By 1912, they were already outnumbered by automobiles; today, there are only 68 licensed carriages and probably a mere 200 horses in the entire city now. Despite peaking at 26 million, the United States population of horses went down to 3 million by 1960. As soon as the economic utility of the animals vanished, they disappeared from public life and the city changed forever essentially overnight.

In 1908, maybe 1% of American households had a car. This number tripled in the 1920s, going from 8 million to around 23 million. By 1948, half of all households had a car; by 1960, it was 75%. The shape of American cities changed completely over this window.

Predicting the future is very difficult, and the core problems in robotics are far from solved, but I think we’re seeing a very similar period of rapid change happening right now. The level of investment and growth in robotics and AI is reaching a fever pitch, well beyond what I expected 1-2 years ago. And, perhaps more importantly, most of what I have believed are substantial blockers to robotics deployments now seem solvable on a technical level:

Robots are relatively cheap, mass-produced, and of increasingly high quality, with a robust supply chain.

Data issues that have stymied robotics learning in the past look addressable.

Core learning technologies — both supervised training on large datasets and reinforcement learning in the real world — have been proven out.

All this means that we should see robots in a lot more industries and parts of society than we’ve ever seen in the past, so let’s talk about the future. But first, let’s lay out the case for robotics optimism — then we can get into what it means.

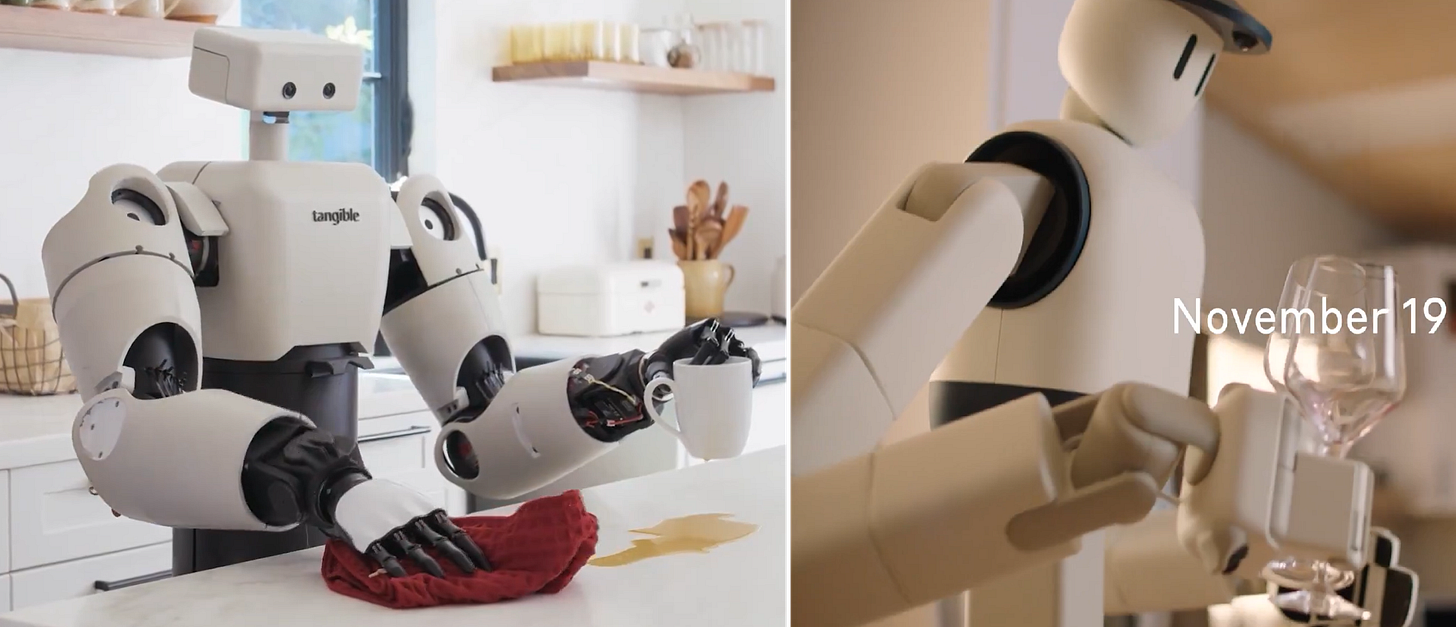

The big story of 2025, for me, is the sheer scale of production of humanoid robots. Companies like Agibot and UBTech are building humanoid robots by the thousands now, and sending them to work in factories belonging to the world’s biggest automakers — companies like BYD.

In general, the number of humanoid robotics companies, and teams working on humanoid robots, is skyrocketing. Most recently, Rivian announced that it is spinning off Mind Robotics, with $115 million in funding. Said founder and CEO RJ Scaringe:

As much as we’ve seen AI shift how we operate and run our businesses through the wide-ranging applications for LLMs, the potential for AI to really shift how we think about operating in the physical world is, in some ways, unimaginably large.

An explosion of investment like this is never due to just one factor. In fact, several things have come together to produce this moment. Quality robots are getting incredibly cheap. The Chinese supply chain is getting very strong, making it easier for new entrants to build at least a v1 of their products. Hardware expertise is getting more widespread.

Techniques for robotics control and learning have become more mature, and have overcome a few major limitations that we’d seen in the past around mobile manipulation and reliable real-world performance. Partly as a result, companies like Unitree and 1x have demonstrated that there is real demand for robots from consumers, with preorders and widespread hype for 1x and exploding G1 humanoid robot sales for Unitree.

Finally, it seems that the robotics “data wall” is becoming less of an issue. Data collection and scaling is much easier than ever. A number of companies like Build and MicroAGI have appeared to scale up human-centric data collection; research work like EgoMimic has provided at least a feasible route to collecting data at scale (watch our RoboPapers podcast episode on EMMA here). Companies like Sunday Robotics are demonstrating how effective scaling with UMI-style tools can be (see our DexUMI episode on RoboPapers here).

When I was in graduate school, this thing cost like $35,000:

And I’m talking just the robot arm - the Universal Robots UR5 - not the gripper, camera, monitor, GPU, et cetera. It was a pretty good platform, but back then the Robotiq 2-finger gripper alone was also probably about $12,000 — totalling about $62,000 when adjusted for the inflation we’ve seen since 2016.

These days, I could buy four Unitree G1s for that price (base model), or, for a slightly fairer comparison, one Unitree G1 EDU plus. I could also buy a LimX Oli. I will soon be able to buy a Unitree H2, a full-sized humanoid robot (probably $60,000-$70,000 USD, tariffs included).

Buying incredibly powerful, capable robots has never been easier: for less than the price of a mid-range sedan, you now can purchase a robot that was impossible even with DARPA funding just a decade ago. And all of these robots have a much more robust ecosystem: the robotics community has, practically overnight, become absolutely massive. Mass production has given us robots which are both cheaper and substantially more capable — as well as just more fun — than was true less than a decade ago.

And this has downstream effects, because a huge part of what makes it hard to automate stuff just comes down to price! Specialized hardware is expensive, but you need specialized hardware less and less — there are so many more options now. The expertise is more available. The hardware is more robust and easier to use. Lower cost makes the entire robotics ecosystem much stronger than it used to be.

We’ve all seen a number of incredible dancing and martial arts videos from companies like Unitree. While these are impressive looking, they don’t demonstrate fundamentally useful robot capabilities, because they don’t interact with the environment. It’s relatively easy to program a robot that doesn’t need to collide with stuff; any dumb technique you can think of these days will work for building a robot that doesn’t need to interact with the environment.

Interacting with the environment, though, is tough. It’s hard to simulate; it requires a ton of real-world data to adapt properly. Getting the correct examples of physical interactions is very hard. I’ve spent much of my robotics career working on long-horizon robot tasks, and at this point the problems are very rarely due to high-level planning (the robot decided to do the wrong thing), but more often due to difficulties with environmental interaction.

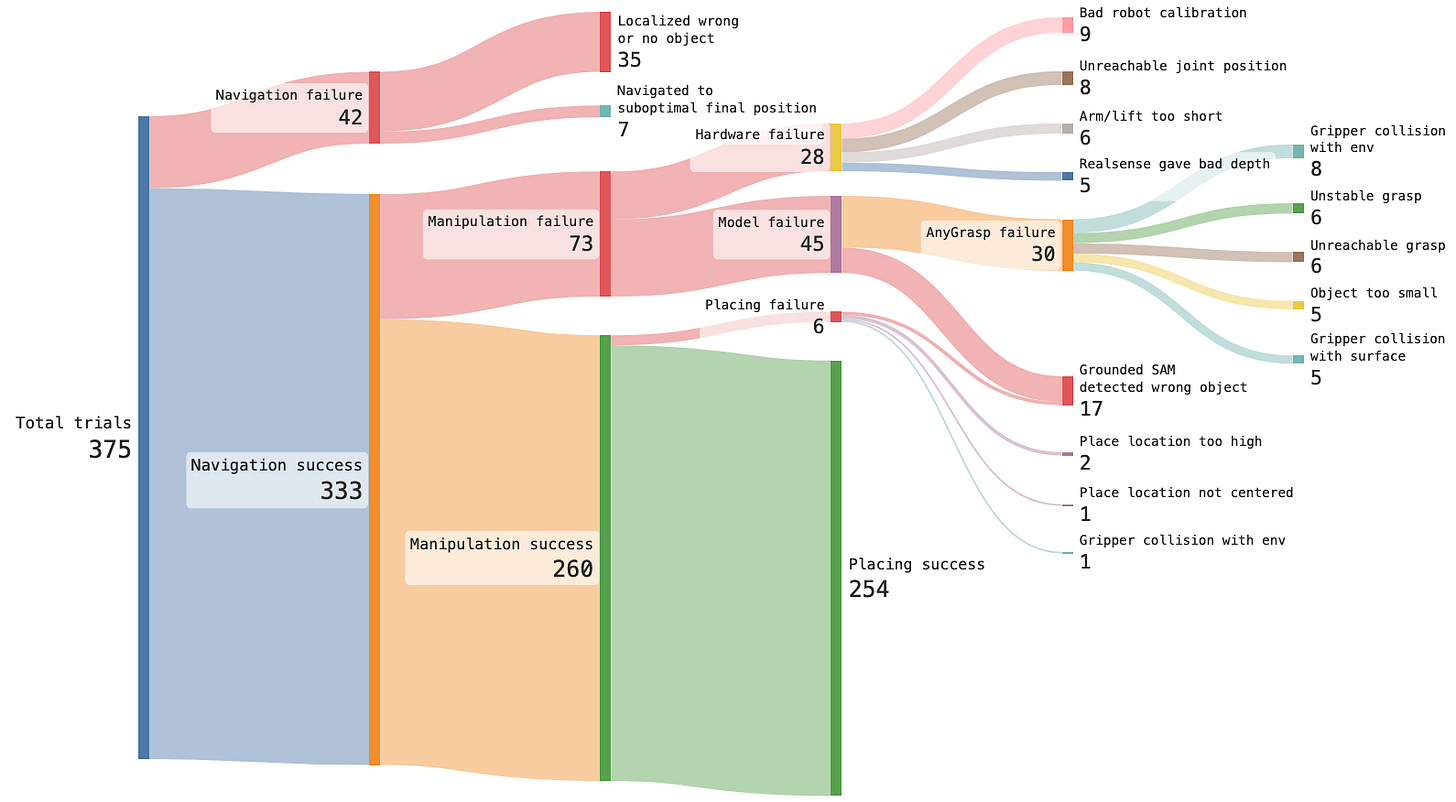

You can take a look at the plot above from the OK-Robot (a 2024 paper) to get a sense for what I’m saying. A lot of the time, the robot can’t reach something (navigation failure); other times the hardware fails; other times it just can’t reliably grasp something due to a model not properly handling the particular combination of environment and object.

If robots could be made to reliably perform real-world manipulation tasks beyond structured picking, this would be a big deal. So I want to draw attention to two specific results that were extremely important this year: whole-body control with mobile manipulation, and real world reinforcement learning.

The video above is from RL-100, recent robotics research from Kun Lei et al. from a variety of institutions but mostly the Shanghai Qizhu Institute. It shows a robot arm working in a shopping mall — an out of distribution environment — while juicing oranges for seven hours.

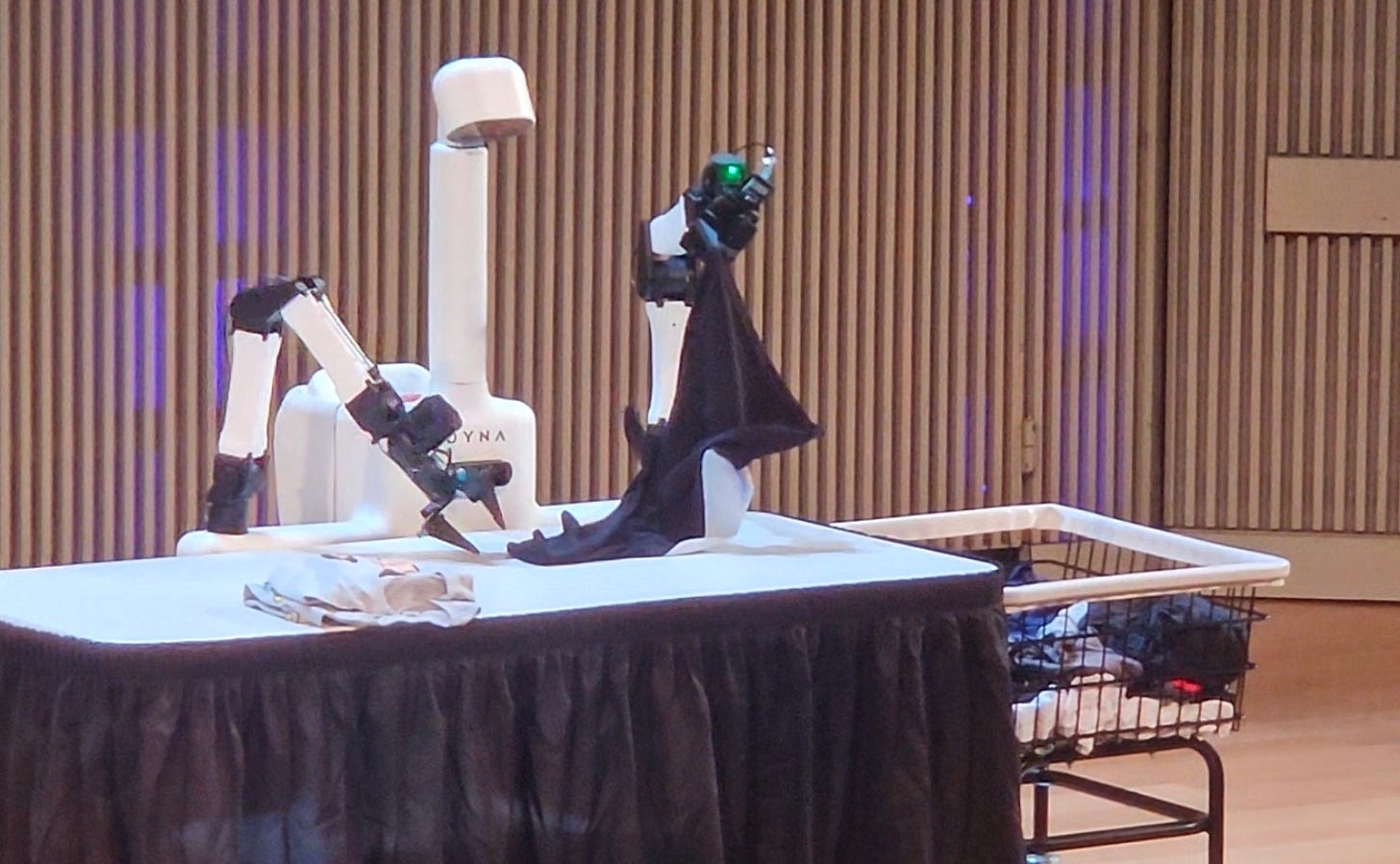

We’ve similarly seen work like pi-0.6* from Physical Intelligence, which showed robots performing tasks like building cardboard boxes and making espresso drinks, reliably, in a way that humans might. And I’ve already written about folding clothes — startup Dyna Robotics started there but has since moved on to demonstrating high reliability in end-to-end learning with other tasks. Now, none of these tasks are revolutionary on their own, but achieving these levels of reliability with end-to-end systems in the real world absolutely is.

More importantly, the idea that there will soon be a recipe for deploying such skills is crucial. By analogy, look at ChatGPT and the broader adoption of LLMs; previously there were many different image- and text-recognition tools. Model large vision-language models like ChatGPT removed the barrier to building systems that leverage text and images; they provide sort of a shared interface. Even if that means running some on-robot RL procedure where someone types 0s and 1s for failures and successes into a spreadsheet, it seems that we could arrive at similarly highly useful systems for robots.

But these advances, just like the ones we’ve seen for large language models, are all likely to be predicated on strong base models, just as we have seen for LLMs. Famously, the reinforcement learning that made Deepseek R1 such a breakout success was only possible because of the quality of pretraining making the reinforcement learning problems tractable.

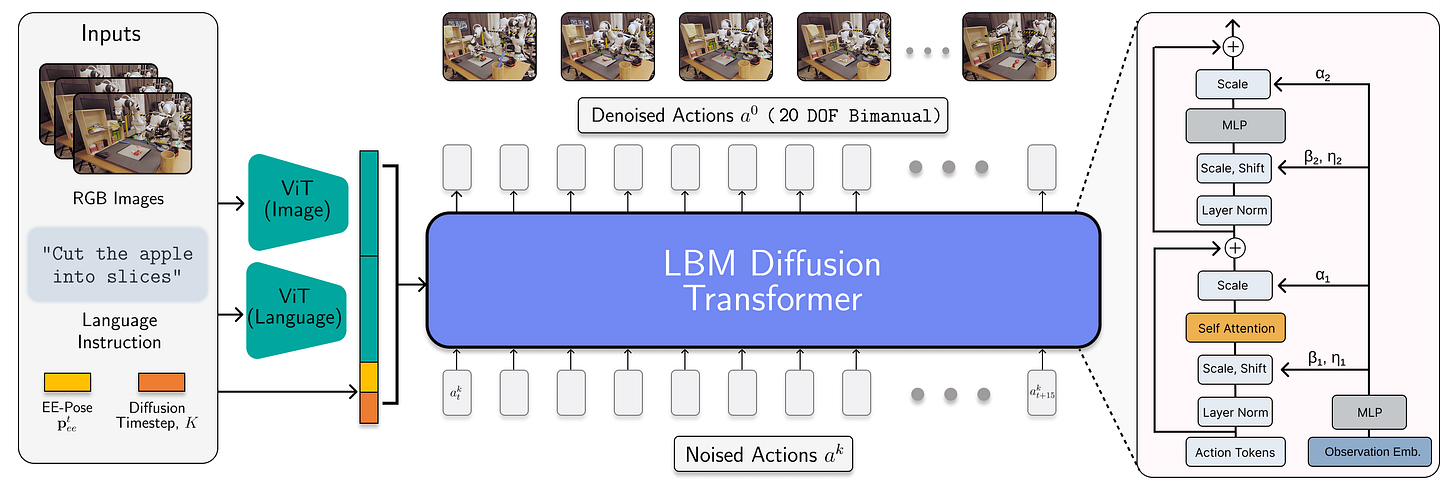

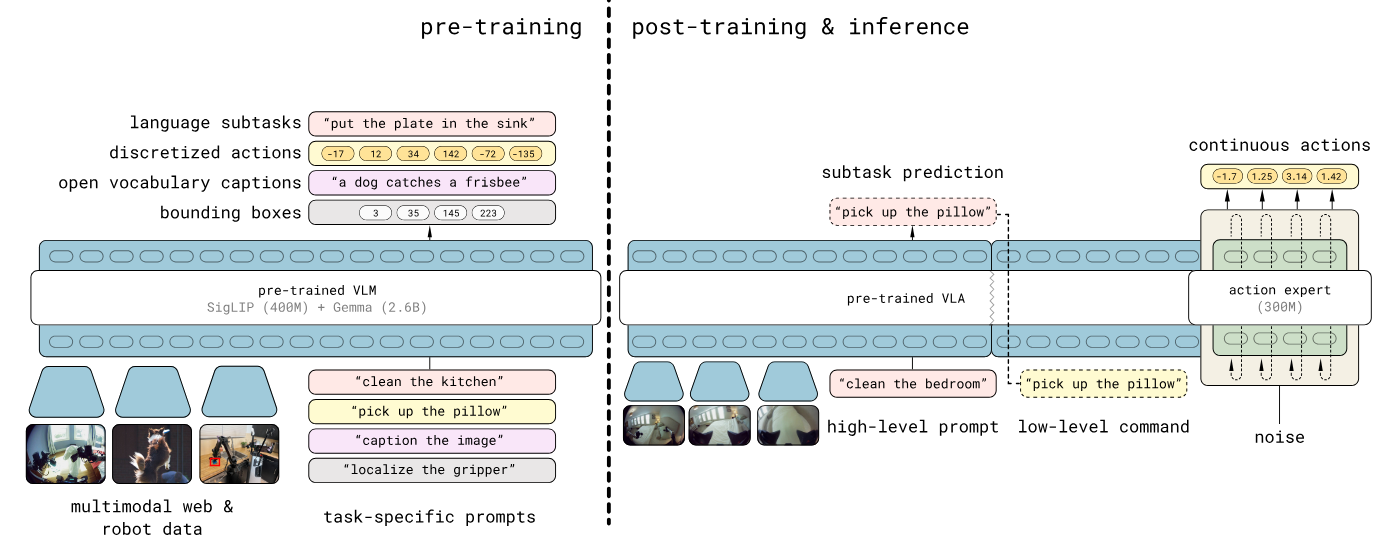

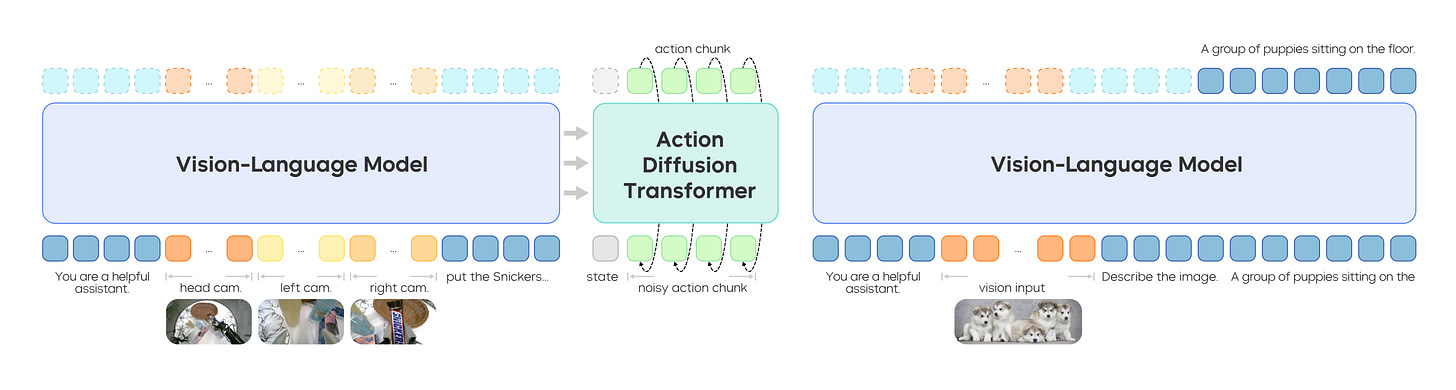

The base models of robotics are usually called Vision-Language-Action models or sometimes Large Behavior Models (there’s actually a small difference here, but they’re accomplishing the same thing). I’ve also written about it as a direction for future VLA research. The question has always been where to get the data.

What’s changed is that now broad, diverse robotics data seems achievable, through a collection of different tools. While certain things seemed to be false starts (mass teleoperation data is too expensive, mass simulation often too difficult to tune for contact-rich tasks), there are other really good options which have come into their own this year: egocentric video data and “UMI”-style tool data.

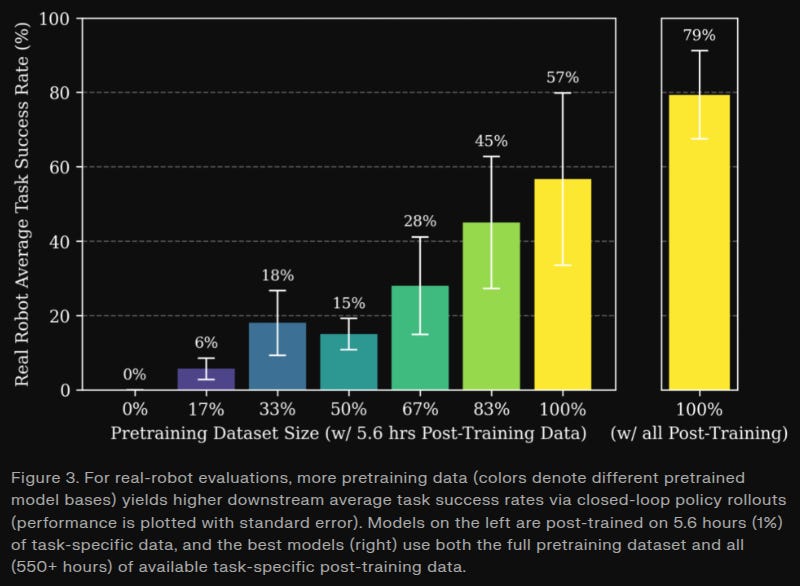

Generalist goes into detail on their recent GEN-0 blog post, describing how diverse pretraining data leads to faster posttraining of their robot models. We’ve also seen from Physical Intelligence that as models scale, they start to learn to treat human data as “just another modality,” meaning that they can start to leverage it to improve performance on various skills. At some point, once we have enough data, this implies that a lot of data-related problems may fall away far faster than previously expected.

A number of companies have sprung up around this idea, including Build, which produces huge quantities of camera-based manufacturing assembly data from human workers, and MicroAGI, which gets rich, high quality data from workers in different industries.

Broadly, it seems more likely than ever that the “eternal” robotics problem of not having enough data, will be solved in the coming years. And unlike in my previous estimates, I no longer believe it will necessarily be some billion-dollar project — which means many companies will be able to build powerful autonomous systems.

Large language models have also made dramatic progress in the last year. OpenAI’s o1 — the world’s first “reasoning model” - launched towards the end of 2024. Its success led directly to the release of Deepseek R1, which was a spectacularly important paper that described publicly a lot of the “secret knowledge” kept in house at OpenAI and has allowed for waves of successive exploration.

And the changes have been extreme. Coding is incredibly different from what it was just a year ago; it will likely never be the same again. Never again will I just write a whole project, token by token, by hand. These changes are appearing in many different industries: people raise concerns about AI replacing lawyers — increasingly many lawyers just draft everything with ChatGPT anyway. Similarly, 67% of doctors use ChatGPT daily, and 84% of them say it makes them better doctors. GPT 5.2 was evaluated on GDPval, a set of economically-valuable tasks, where it achieved equal or better performance than an in-domain human expert 70.9%.

Large language models are already significantly changing the way people work and rewriting the economy, like it or not. And these changes seem to be propagating far faster than the changes we saw with automobiles at the beginning of the 20th century, having propagated through society with all the speed of the internet. Robotics won’t spread so fast, but unless serious obstacles manifest (such as a total collapse of funding for R&D), it seems plausible there will be similar changes in the physical world.

To go back to the metaphor at the start of this blog post: when horses vanished from American cities, they didn’t just lose their jobs. The whole infrastructure of cities changed: hay and stables were replaced by gas stations and parking garages. Manure was gone from the streets, replaced by exhaust fumes. The feel of a city, even walking around on foot, now revolves around cars, with wide, flat asphalt roads and traffic lights on every block. Similarly, if the “optimistic case” from this blog post holds true, we should see significant changes in the fundamental details of life.

So, to recap: we have seen a year of dramatic robotics progress which for the first time showed the viability of long-running end-to-end robotics manipulation, at the same time the cost of robotics hardware is collapsing and its quality is exploding. We have seen dramatic changes in the world of purely-informational artificial intelligence, through reasoning models and agents.

I believe I have motivated this “optimistic case” well enough now that I am allowed to speculate a bit, as I promised at the beginning of this blog post. To start, we may make a couple assumptions about robotics over the next several years:

The robotics “data gap” will continue to close, and robotics will start to pick up speed due to the combination of more robots and more tools for making robots possible to use and deploy

AI will be at the heart of this — both reinforcement learning and imitation learning will be key parts of the solution, as elaborated in my previous blog post on VLA research directions

This means that a lot of areas of robotics which were previously inaccessible to automation soon will be. In fields like construction, we have thus far been limited to incredibly simple and structured pieces of automation: specially-built roofing robots, for example. Similarly, much of manufacturing is already automated, but that automation relies heavily on specialized systems, sensors, end-effectors, and machinery. All of this makes automation extremely expensive.

At the same time, the labor markets for fields like construction and manufacturing are getting worse. The world has filled up in a way; our countries are graying. We expect the ratio of workers to retirees to go down, requiring each individual worker to be far more economically productive. Those same retirees will need care and companionship that humans are unlikely to be willing or able to provide. All of this means that the world of 2030 will be far more robotic than that of today.

By 2030, users will be able to create and share their own use cases, as this is where true explosive growth starts to happen.

I expect we will see far more robots essentially everywhere. Waymo and its competitors will expand to more and more cities; fewer people will use their personal vehicles to get around. If they do, their vehicles will be using Tesla or Wayve autopilot systems to get around.

Robots will be in homes. They may or may not be humanoids. But they’ll be able to perform a wide range of simple manipulation tasks, things like picking up and perhaps putting away the dishes. They’ll cost less than a car, possibly in the $10,000-$20,000 range for a very good one. Robot production will still be ramping up this point, so it’s probably still less than 1% of households that have an in-home robot — but it’s going to be rapidly increasing into the 2030s, until it reaches similar levels to cars by 2040, with 50% or more owning an in-home robot that can help do chores.

These home robots will often be companions first; modern AI is extremely good at companionship. It is striking to me how much for example my two year old daughter likes to interact with even very simple home robots like Matic and Astro; more capable and intelligent LLM-powered home robots will be far more compelling friends and “pets.”

Most importantly, this will also lead to the “iPhone moment” for robotics, which is when acceleration will really take off. Some — such as Sunday Robotics founder Tony Zhao — have publicly alluded to this moment coming. What we hope is that by 2030, users will be able to create and share their own use cases, as this is where true explosive growth starts to happen.

In manufacturing and industry more broadly, we’re already seeing “systems integrators” start warming up to widespread use of end-to-end artificial intelligence. As the core technical competencies for deploying robotics models and post training them for specific tasks start to diffuse, I expect this to become very common.

Perhaps by 2030, you will order a set of robots for your factory and hire a consultant to train them for a couple days if you’ve never done so yourself. Eventually, though, this seems like an economic efficiency that will largely be done away with. You don’t usually hire an external contractor to integrate an LLM into your workflows; robots should be no different.

I started this post with an anecdote about horses being replaced by the automobile, but so far I really haven’t discussed what, exactly, the horses are that are being replaced. These metaphorical horses aren’t people, not exactly, but they are jobs currently done by people. Software engineering, for example, is clearly harder to break into now than it used to be. An individual experienced programmer is so much more productive with AI as a “force multiplier,” which means that less people are necessary to build and deploy complex software products.

We should expect to see similar trends across basically every industry: more highly paid experts being far more productive, building more things, but each individual set of expertise being basically priceless, with robots handling more and more of the easily-replaceable labor. We should not fear this: in the developed world, working hours have largely been on a downward trend for decades, and it seems likely this will continue. Many human jobs will amount to handling the long-term planning and coordination that AI and robots seem persistently bad at, and intervening when they fail; but this should make for comparatively easy and low-stress work for a great percentage of the workforce.

It’s strange to look back at my own predictions for robotics from the end of 2024. Back then, one of my chief concerns was how to build scalable “world representations” for long horizon reasoning. This remains a concern to me; I’ve honestly seen basically no significant progress in this space. There are impressive 3d world models now, like that of World Labs, but these are all generally creating single scenes, not modeling their evolution in response to new sensor data. For true embodied general intelligence, we still need to address these fundamental questions about how robots will represent their knowledge of the world over time.

In some ways, it’s a good thing: the blocker for deploying long horizon reasoning has never been that long horizon reasoning is all that hard, it’s always been that execution is hard and that robots break (see, again, the Sankey diagram above from OK-Robot).

This also will still require lots of funding. Fortunately, it seems that many investors and billionaires with deep pockets — Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk, and others — are “all in” on artificial intelligence and robotics. Very likely, the money will not run out. But if it does, all this could come to a premature end.

And finally I worry about the closing-off of ecosystems. Open robotics innovation right now is championed, largely, by Physical Intelligence and NVIDIA, with some great recent entrants from Amazon FAR. While many of these problems are being solved, we still need new ideas and open dialogue to solve them — if all our doors and windows close, it’s possible the field stagnates and nothing gets accomplished.

With robot hardware getting so much better, with methods becoming mature and real-world results and long-running demos becoming somewhat common, I’ve never been more optimistic about what robotics will be capable of.

Part of the point of writing this is to point out how fast things have changed. And this is not unprecedented! I started this blog post with an anecdote about the horse being replaced by the automobile over just a couple decades. It’s not unreasonable to think that — in a lot of ways — we’re heading for such a moment. Not next year, not in two years, but over the next decade? It seems inevitable.

Basically all robotics problems get easier at scale: hardware related, deployment related, and data related issues all become much more tractable as soon as there are a lot of robots out there in the world.

I believe very strongly that we’re on a great trend, that these technologies will diffuse through society over the next 5-10 years, and that the future bright. But we’re headed for a very different world than the one we live in now, and that’s something we’ll also need to wrestle with over the coming years.

]]>

The future of industrial production is automated. From our ports to trucking and last-mile delivery, robots are now involved in nearly every part of bringing people the products that they want. And yet in a lot of cases the production of these products themselves is not yet automated; they are still built by specialized human workers. Even in wealthy, developed countries like the United States many things that seem as if they should be automated are not.

Take the example of Nike trying to near-shore production of shoes from Vietnam to Guadalajara, Mexico, as described in this Wall Street Journal article by Jon Emont. Shoe manufacturing relies on an army of skilled workers to perform fine manual labor, stitching and gluing a very wide variety of shoes together.

Ultimately, this effort was unsuccessful; Nike ended up closing the facility, and most shoes are still made by hand as of the writing of this article. And Nike isn’t the only example; small manufacturers in the United States rarely employ automation, far less than in near-peer countries like China or Germany.

There are a variety of reasons that automation seems to be taking off at different rates, ranging from technical to economic. Let’s go over some of the whys here: why automation is hard, where it fails, and why it seems to be moving faster in some areas than others.

If you like this blog, please consider subscribing, liking, or leaving a comment. Liking and subscribing helps others find these posts!

Industrial automation actually works very well within its narrow operational constraints. So-called dark factories have existed since 2001, when FANUC began lights-out operations at its flagship facility, with robots producing other robots wholly in the dark for up to 30 days at a time, completely unmanned.

These dark factories have become an iconic feature of Chinese industry, with giants like Xiaomi and BYD increasingly employing them to mass-produce products like smartphones and cars.

But all of these products have something in common: with smartphones, or cars, or industrial robots, you might be building millions of units of product with very few variations. This justifies the larger up-front cost of traditional automation, which involves carefully designing assembly lines, planning robot placement, and even planning individual movements the robots will be making in perfect synchrony months ahead of time.

This is, to say the least, an incredibly expensive undertaking. It’s the work of systems integrators, companies that focus on building a particular class of robotics automation solutions. They will plan camera placements, write code, hook up sensors, design custom tools or parts — whatever is necessary to produce the perfect fully-autonomous production line.

Above: video of a small Chinese machine shop by Marco Castelli on X

Benjamin Gibbs of Ready Robotics wrote a thread on X a while ago, listing reasons why you don’t see more robots deployed, especially looking at small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). In short:

Skepticism: the idea that many people know someone or have themselves tried to deploy a new industrial robot, and have not gotten a good return on their investment.

Opportunity cost: for a small, low-margin producer, spending $50,000 on a new robot makes a lot less sense than buying a new tool (also very expensive!) which can open up new revenue streams for the company

Software complexity: note that this is not the complexity of programming the robot, but of integrating various vision and safety systems, connecting to industrial PLCs, and so on. Each integration can be a massive undertaking with many different programming languages and (usually poorly documented) software packages involved.

Tooling design: industrial robots, as they are currently used in the United States, require very specialized end effectors to be useful. There is still no “universal” robot tooling; you cannot just order these parts off the shelf. Companies like Right Hand Robotics which once aimed to build more broadly-useful grippers and tools have always ended up narrowing their ambitions substantially.

Parts presentation: basically, the “art” of building a reliable input system for parts to arrive at the robot; almost every one of these has historically been custom-made and is therefore wildly expensive.

Electrical complexity: because there are so many custom parts and sensors, a shop looking to automate will need a custom electrical panel. They’ll need someone with wiring experience that they almost certainly lack in-house.

Let’s go back to the Nike example above. Their hope was that they could reproduce successes in building microprocessors, but applied to this new domain. Shoes are representative of a lot of the issues that robotics problems struggle with:

The wide variety of shoes produced, all with subtle differences, increases the human effort necessary to handle the full range of products during the process of automation systems integration

Similarly, the fact that shoes are made out of deformable materials means that the number of special parts and designs needed to fixture a shoe properly to grasp it 99.99% of the time and automate a full production line is extremely high

Safety sensors and integration requirements exist for partially automating production, which would not exist for a setup that’s not automated

Integrating all the specialized hardware used by a traditional systems integrator will be nearly impossible.

And the problem gets worse.

In 2021, China overtook the United States for number of robots deployed in manufacturing. By 2025, they’ve also overtaken anyone else, becoming the leading user of industrial robots in the world. This is not because of some technical edge — the bleeding edge of technology exemplified by companies like Physical Intelligence remains solidly American — but because of a complex ecosystem that enables production and deployment of robots economically and at scale.

As Andreesen-Horowitz noted in their report on robotics automation:

There are no “dark factories” in the United States. The closest that we have is Tesla’s Gigafactory Nevada, which is 90 percent automated. No other major manufacturer comes close.

Deployment costs and “cost disease” are endemic in many areas of American industry, and manufacturing appears to be no exception. As a result of these deployment hurdles, we often see that companies deploy robots only because they are forced to, usually by labor shortages.

It’s also noteworthy that, as mentioned above, current industrial automation requires a large number of custom parts, which means that the best returns will only appear at the very largest manufacturing scales. Without a robust ecosystem for custom systems integration work and a broad depth of expertise in the market, integration costs will remain extremely high.

So, in a way, it could be argued that we don’t use many robots, because costs are high, and costs are high because we don’t use many robots. This is a place where government action has worked in China, where there are often 10-20% up-front cash subsidies available for manufacturers. While the USA has similar incentives American subsidies take the form of tax breaks (such as Section 179), which necessitate extra legal fees, overhead, and for the company to take that extra cost burden ahead of time anyway only to be “paid back” later. It’s perhaps a less efficient way for the government to spend the same amount of money.

In the end, we have two types of problems: shortcomings of current technology and shortcomings of the broader economy that make automation less tractable in the united states. Aggressive competition in manufacturing has led to better returns on scale, both internally to companies and to the country as a whole which benefits from robust supply chains, expertise, and labor markets.

But technology, here, might be a way out. The factory of the future probably does not use the wide range of specialized sensors and fixtures that Ben Gibbs mentioned in his thread. Modern vision-based AI systems are pretty good at handling deformable materials like clothes. Companies like Dyna and Physical Intelligence have shown dual-armed mobile platforms that are both reasonably affordable and capable of performing an extremely wide variety of useful tasks to a high degree of reliability, if not particularly quickly (yet).

The difference here is massive. These newer, lower-cost robots are safer to be around, they’re cheaper to replace, and they don’t need the massive diversity of custom sensors or fixtures to work properly. Instead, because they work by seeing the world like humans do, they can be placed in a production line more or less the way that humans are, with only a fairly labor-intensive bringup process to teach them a new skill. But note that this bringup process is still less labor intensive than the current arduous process undertaken by the systems integrators we discussed above!

Perhaps in the farther future, we’ll see things like the MicroFactory take off: a bunch of cheap, modular robotic cells designed to be deployed in a controlled work cell, so that you could easily parallelize reinforcement learning training and deploy the robots at scale on a large production line. We’re already seeing companies like Standard Bots working to reinvent the formula.

Real technical challenges remain around speed, safety, and the general capability of these robots — as well as how to make their training more scalable and make the hardware more reliable. But the future of robotics manufacturing, it seems, will come from Silicon Valley and Austin, Texas, not the traditional manufacturing centers of the US, and it will be software-first.

If you liked this post, please like, share, and subscribe; or leave a comment with your thoughts below.

]]>

Google has a new paper called Nested Learning which aims to enable lifelong learning in artificial intelligence by framing the machine learning optimization problem as a set of nested sub-problems [1]. In the authors’ words:

We introduce Nested Learning, a new approach to machine learning that views models as a set of smaller, nested optimization problems, each with its own internal workflow, in order to mitigate or even completely avoid the issue of “catastrophic forgetting”, where learning new tasks sacrifices proficiency on old tasks.

For robots and other artificially intelligent agents to be deployed “in the wild,” they will need to be able to learn on the fly, while not forgetting all of the other things they’ve already learned.

The way we usually do this right now is through clever tricks of context; for example, when you talk to ChatGPT, it will save additional memories as text. I actually have a really dumb version of this implemented in a Discord chatbot here if you want to see how well it works by experimenting on your friends and family.

But this has its limits. Context lengths grow, and memories require more and more “compression.” This form of memory is essentially just a more elaborate system prompt in a lot of ways, and so nothing fundamental will change. Ideally, we would see a version of this where the weights of the neural network themselves change over time, something more like how humans learn over time.

This is a problem we call Continual Learning or Lifelong Learning. If you want to read a bit more about continual learning in computer science, and what it might mean for human learning, you can check out this blog post by Beren Millidge called “Continual learning explains some interesting phenomena in human memory.”

The core insight in this work is that by treating the whole AI learning problem as a set of nested sub-problems, which makes it possible to avoid a crucial issue with current continual learning approaches. Let’s go lightly over how.

This is pretty different from my usual type of post, so maybe take a look at some other posts before clicking subscribe below (like this one or this one):

The core problem we want to solve with lifelong learning is called catastrophic forgetting. Let’s walk through a naive solution to see why.

Imagine I have a neural network which I’ve trained to perform some task, like say pick up cups around my house and put them back in the cabinet. I’ve collected a great dataset for cups: I have a whole variety of cups of different sizes and shapes and colors. I have all the places where they might go: these go in a cabinet, these fancy cups in a display case, and so on. Great. Call this dataset A, and assume I have some policy trained on this A.

Now, I extend this with new data to pick up toys off of the floor and put them in their boxes. I collect a new dataset with all kinds of children’s toys: action figures, stuffed animals, whatever. With them I collect a new dataset of demonstration locations to place these objects. Call this dataset B.

I continue training my model, which was originally trained on A, but now I am only training it on B. Unsurprisingly, when I next try to train on A, I see that I’ve now lost all performance on A — my robot can no longer put away cups properly.

Now, I already know the solution to this: I have to train on both A and B. The problem is that as I add more datasets — C and D and E and so on — the amount of data that I have to train on becomes cumbersome. I start to run into model capacity issues, or inference becomes slow, or I just can’t train on all of these fast enough.

Realistically, I want some way of updating my policy with a new dataset without hurting its performance on old datasets, but also without fully retraining on all my various datasets. The naive solution here — the most common and usually best solution — will be to just sample from all of the different datasets so I’m always retraining on a little bit of everything, according to my other constraints.

But that’s an awkward solution that requires you to store infinite data forever, so let’s see if these Google researchers can come up with something better.

In general, we solve this problem through modularity. In what limited work I’ve done on continual learning [2], for example, the proposed method resulted in multiple parallel robot policies, each of which was specialized to a different setting.

But that’s not really how the human brain works. We have memory that operates at many different scales: some longer term, some shorter term. Current transformers only experience the present: they basically have some baked-in knowledge encoded in weights, and they have their context, and that’s it.

The key insight here is that momentum-based optimizers like Adam are, in an of themselves, a sort of associative memory — basically a model. And so we can pose a learning problem as a set of nested optimization problems, all running at different speeds:

Inner loops update rapidly to capture new information (like the locations of the toys we wanted to grasp, from our example above)

Outer loops update slowly, capturing more general information (the structure of the home, perhaps).

This means that the slower outer loops can anchor new information and prevent the model from forgetting everything.

The core claim of the paper is that architecture is an illusion: that both optimizers (Adam, for example) and neural networks are the same thing: an associative memory. Since we will be talking a lot about learning and memory, the authors provide us with this helpful definition:

Memory is a neural update caused by an input, and learning is the process for acquiring effective and useful memory.

An associative memory, then, is going to be something which maps between different sets of keys and values:

This is an incredibly broad definition, which is sort of the point. So Attention is an associative memory mapping tokens to other tokens; Momentum (as in SGD) is a memory mapping gradients to updates. Optimizers like SGD are just very simple associative memories, which the authors proper replacing with “Deep Optimizers” that learn how to update inner networks.

So, training a single neural network as building a mapping between the data points in your training dataset and their local surprise signal in representation space (i.e. how well they match their objective), just over the training dataset examples.

This part is pretty straightforward interpretation of LLM training. Where it gets more interesting is in the next layer; a momentum-based optimizer then becomes a second-level associative memory, where the outer layer is updating the weights with based on the inner-level memory (again, basically prediction error).

We can follow this logic to phrase a machine learning problem as a set of nested optimization problems, where at each level it isn’t just learning a task but also learning how to learn the task. These levels all operate at different update rates — again see the analogy to the human brain above — with outer/higher level loops updating less frequently.

The authors go into more detail talking about how they can represent many well-known optimizers as special cases of nested learning, and go on to propose more expressive versions of optimization and of the underlying memory operation. They also propose HOPE.

HOPE is a “Self-Referential Learning Module with Continuum Memory,” which here means that it’s a chain of neural network blocks updated at increasing frequencies as they are nested deeper and deeper. To understand why, let’s consider the case of learning a Transformer for language prediction.

In a “normal” Tranformer trained with a discrete train and eval phase, we have two time frequencies that we care about; general, high level information is only encoded once, at training time, and local information is only encoded in the context window (hence in-context learning). But with HOPE, we have many modules, each learning how to update the one below it, and operating at different rates, which makes it much more adaptable.

Their proposed architecture builds on Titans [3]. Titans are a new class of model designed to improve memory, enabling remembering and forgetting over time (remember this is generally not something transformers do — they just rely on their long context windows!).